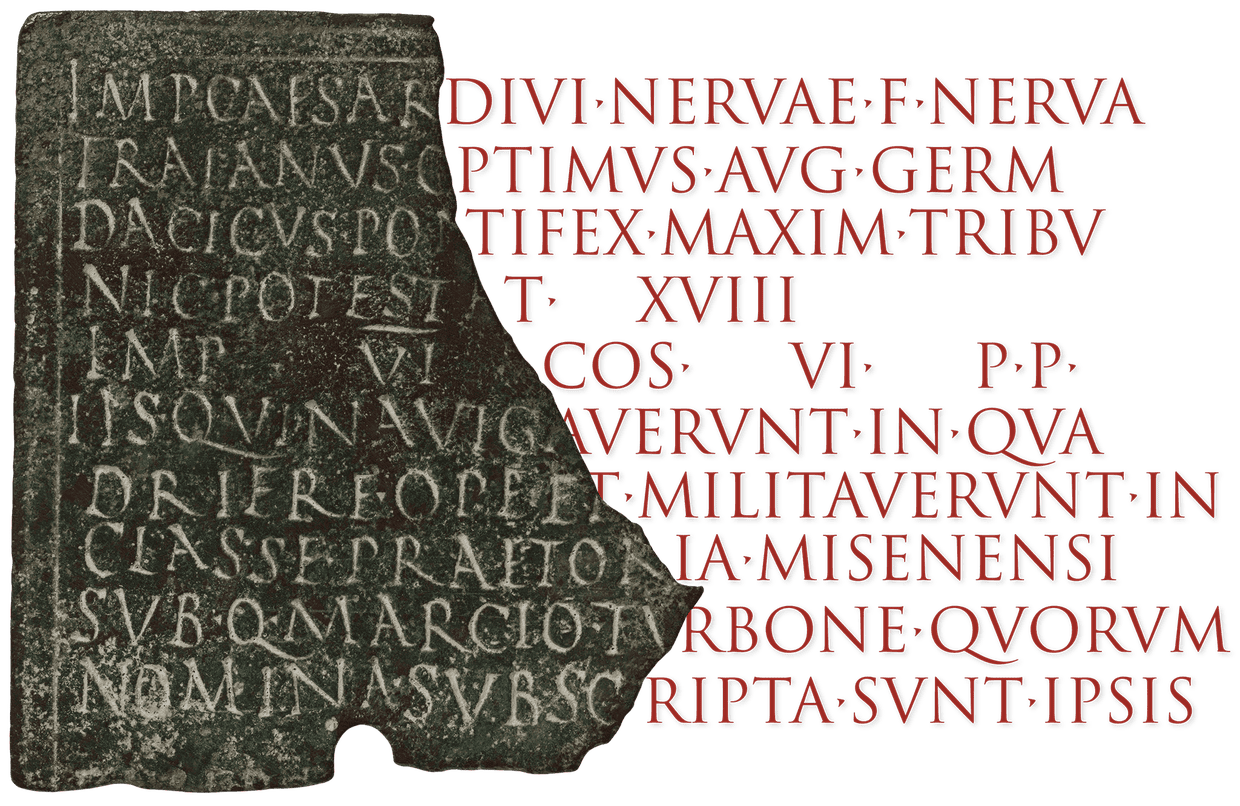

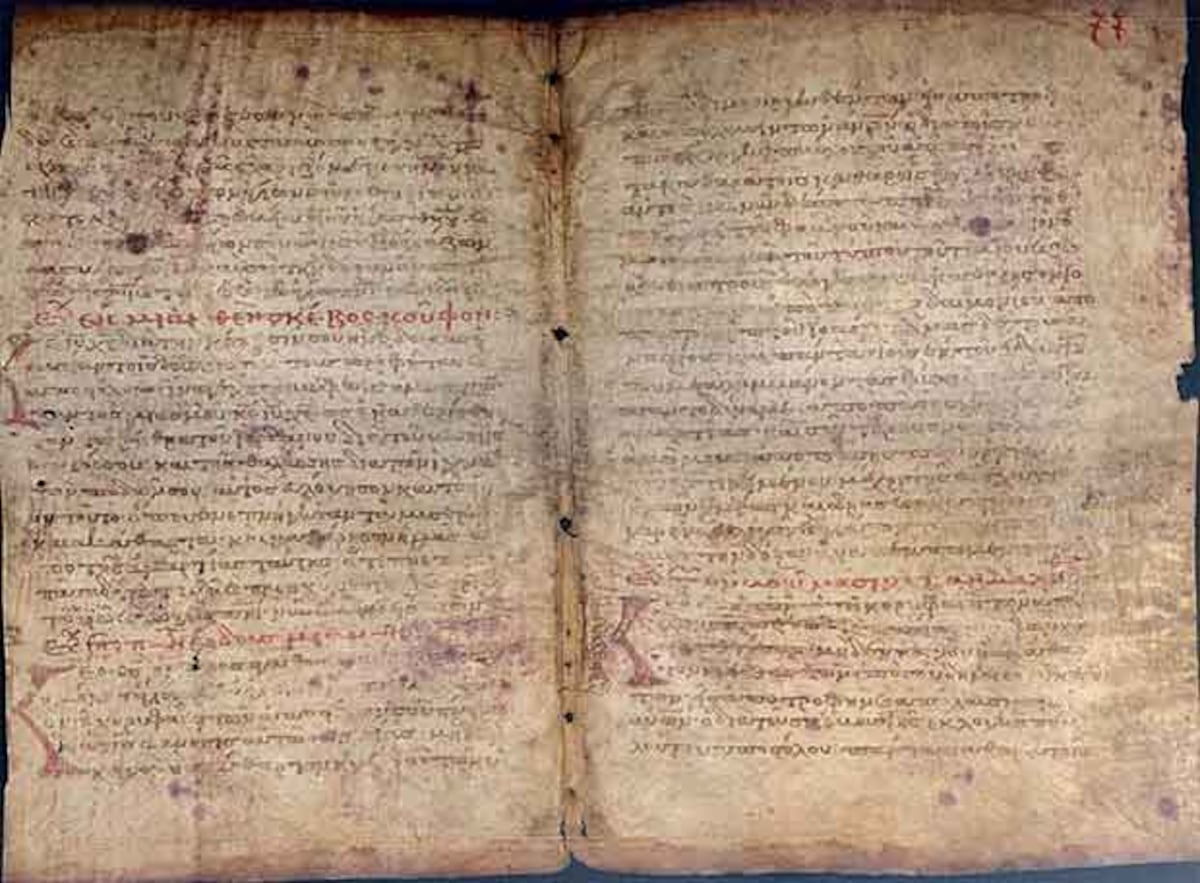

Photo: R.L. Easton, K. Knox, and W. Christens-Barry/Propietario del Palimpsesto de Arquímedes.

AI was used to translate this palimpsest with texts by Archimedes.

In general, I am wary of artificial intelligence, which one of its first developers has warned is dangerous. I use it to ask Google questions, but it’s a real nuisance in the English as a Second Language classes where I volunteer. Some students are tempted by the ease of using AI to do the homework, but of course, they learn nothing if they do that.

There’s another kind of translation, however, that AI seems good for: otherwise unreadable ancient texts.

Raúl Limón writes at El País, “In 1229, the priest Johannes Myronas found no better medium for writing his prayers than a 300-year-old parchment filled with Greek texts and formulations that meant nothing to him. At the time, any writing material was a luxury. He erased the content — which had been written by an anonymous scribe in present-day Istanbul — trimmed the pages, folded them in half and added them to other parchments to write down his prayers.

“In the year 2000, a team of more than 80 experts from the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore set out to decipher what was originally inscribed on this palimpsest — an ancient manuscript with traces of writing that have been erased. And, after five years of effort, they revealed a copy of Archimedes’ treatises, including The Method of Mechanical Theorems, which is fundamental to classical and modern mathematics.

“A Spanish study — now published in the peer-reviewed journal Mathematics — provides a formula for reading altered original manuscripts by using artificial intelligence. …

“Science hasn’t been the only other field to experience the effects of this practice. The Vatican Library houses a text by a Christian theologian who erased biblical fragments — which were more than 1,500-years-old — just to express his thoughts. Several Greek medical treatises have been deciphered behind the letters of a Byzantine liturgy. The list is extensive, but could be extended if the process of recovering these originals wasn’t so complex.

“According to the authors of the research published in Mathematics — José Luis Salmerón and Eva Fernández Palop — the primary texts within the palimpsests exhibit mechanical, chemical and optical alterations. These require sophisticated techniques — such as multispectral imaging, computational analysis, X-ray fluorescence and tomography — so that the original writing can be recovered. But even these expensive techniques yield partial and limited results. …

“The researchers’ model allows for the generation of synthetic data to accurately model key degradation processes and overcome the scarcity of information contained in the cultural object. It also yields better results than traditional models, based on multispectral images, while enabling research with conventional digital images.

“Salmerón — a professor of AI at CUNEF University in Madrid, a researcher at the Autonomous University of Chile and director of Stealth AI Startup — explains that this research arose from a proposal by Eva Fernández Palop, who was working on a thesis about palimpsests. At the time, the researcher was considering the possibility of applying new computational techniques to manuscripts of this sort.

“ ‘The advantage of our system is that we can control every aspect [of it], such as the level of degradation, colors, languages… and this allows us to generate a tailored database, with all the possibilities [considered],’ Salmerón explains.

“The team has worked with texts in Syriac, Caucasic, Albanian and Latin, achieving results that are superior to those produced by classical systems. The findings also include the development of the algorithm, so that it can be used by any researcher.

“This development isn’t limited to historical documents. ‘This dual-network framework is especially well-suited for tasks involving [cluttered], partially visible, or overlapping data patterns,’ the researcher clarifies. These conditions are found in medical imaging, remote sensing, biological microscopy and industrial inspection systems, as well as in the forensic investigation of images and documents. …

“The researchers themselves admit that there are limitations to their proposed method for examining palimpsests: ‘The approach shows degraded performance when processing extremely faded texts with contrast levels below 5%, where essential stroke information becomes indistinguishable from crumbling parchment. Additionally, the model’s effectiveness depends on careful script balancing during the training phase, as unequal representation of writing systems can make the deep-learning features biased toward more frequent scripts.’ ”

More at El País, here. What is your view of AI? All good? Dangerous? OK sometimes? I can’t stop thinking about the warning from Geoffrey Hinton, the ‘godfather of AI,’ that it could wipe out humanity altogether.