Photo: Rasha Al Sarraj.

Ghulam Hyder Daudpota teaching his craft to students at a ceramics class in Karachi.

Part of the effort to save artistic and cultural treasures has to be keeping alive the ability to make them in the future. It involves passing on the skills to new generations. Consider today’s story.

Saeed Kamali Dehghan reports at the Guardian, “The small city of Nasarpur in Pakistan has a centuries-old reputation for its ceramics. That’s why, when the ceramic worker Ghulam Hyder Daudpota decided to come all the way to London to master his craft, he says ‘it seemed futile.’ But, he adds: ‘It turned into a life-changing opportunity.’

“Daudpota grew up with eight siblings in a city where the mosques and shrines are embellished with terracotta and blue glazed tiles, known as the art of kashikari. He spoke little English until the age of 27 and his parents had ‘no deep pockets’ to pay his tuition fees.

“But the talented Pakistani secured a full scholarship at the King’s Foundation school of traditional arts (KFSTA) in east London, before returning to his country and helping to revive the dying craft.

“ ‘Kashikari is ubiquitous across [the province of] Sindh, but when I was growing up it was considered a dying craft and only a few craftsmen were practicing. If it wasn’t for my time at KFSTA, I wouldn’t be where I am at the moment,’ Daudpota says from his Nasarpur workshop, which now employs 40 people.

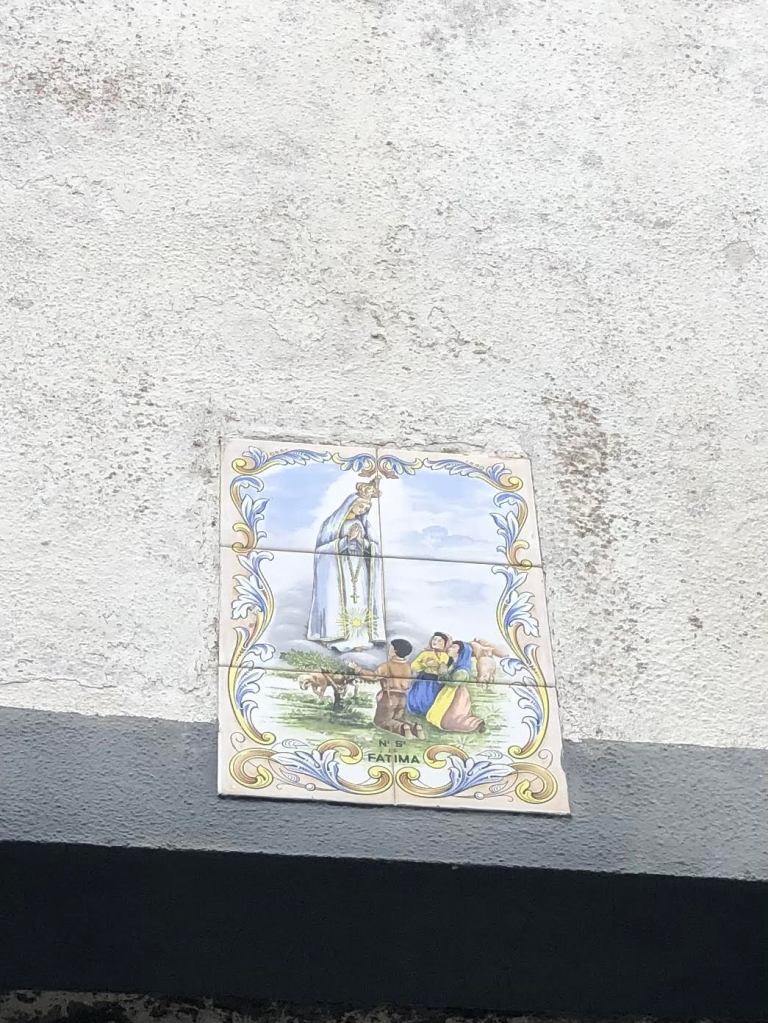

“Believed to have originated in the Iranian city of Kashan, kashikari involves making biomorphic patterns on terracotta clay by dabbing graphite on perforated paper, before applying turquoise metallic pigments found in copper and cobalt oxides.

“ ‘If you go back 100 years, we had a variety of glazes and techniques – masterpieces that we see today in Shah Jahan mosque in the city of Thatta – but we had no proper patronage and we lost our skills, we lost our knowledge,’ Daudpota says.

“Daudpota has since worked on designs at Islamabad airport, Pakistan’s pavilion at Dubai Expo 2020 and on restorations at prominent mosques and mausoleums. In 2010 he was awarded the Jerwood prize for traditional arts for a tile fountain inspired by kashikari panels found in Nasarpur’s old mosque. Daudpota sold the fountain for £5,000 [~$6,600] and received £2,500 in prize money, which he took back to Pakistan and opened a workshop.

“It was a long way from what he had expected from life. Daudpota did not perform well at school and his parents apprenticed him to a local craftsman. An encounter while working on a commission at a private mansion changed the course of his career. ‘It was a turning point in my life,’ he says.

“The house was owned by a teacher at the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore. He told Daudpota that his experience would qualify him to study for a master’s degree, provided he learned English within the next four months. He took classes at sunrise every day and passed the test.

“The NCA has a longstanding arrangement with KFSTA, sending one student to London every year for almost three months. Daudpota was chosen for the 2008 program. …

“KFSTA promotes ‘the living traditions of the world’s sacred and traditional art forms,’ such as Persian miniature painting, Moroccan zellige mosaic tilework and Egyptian Mamluk woodcarving. …

“ ‘Teachers in my country were discouraging me from pursuing traditional arts; they were saying it was primitive. The school broadened my perspective, and gave me the training platform to understand how we can turn a dying tradition into a living tradition.’ ”

More at the Guardian, here. No paywall. Donations encouraged.