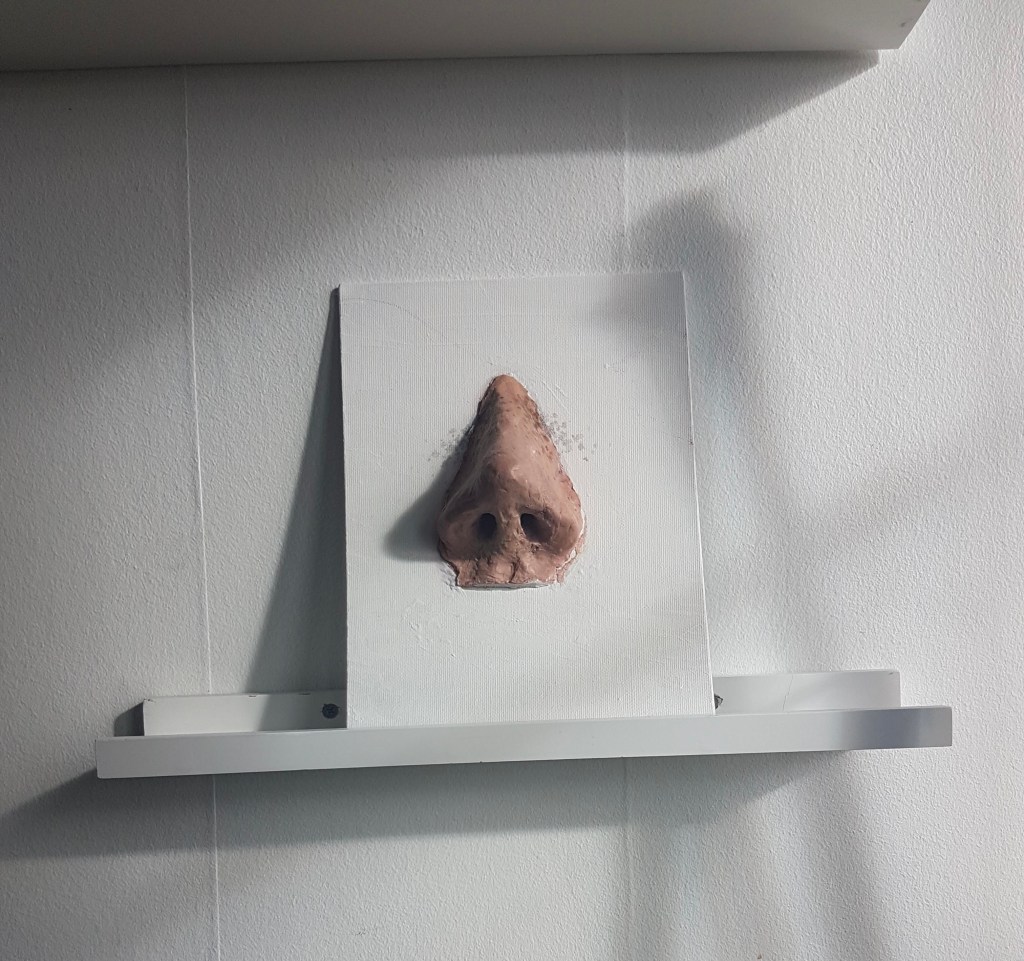

Photo: USA Dance.

A dance competition for seniors.

One of the exercise classes I like at my retirement community is called Movement for Body and Brain. It is led by a dancer who is trained in a variety of related disciplines, including exercise for Parkinson’s patients. I started attending because she has the best music of any of the classes. I stayed because it’s great exercise.

An article at the Washington Post by columnist Trisha Pasricha, MD, explains why movement like dancing is good for your health.

“This fun hobby,” the Post claims, “may reduce your risk of dementia by 76 percent.”

Dr. Pasricha writes, “Dancing combines some of the best elements known to be associated with longevity: exercise, creativity, balance and social connection. … One study found that people who danced frequently (more than once a week) had a 76 percent lower risk of dementia than those who did so rarely.

“In the early 1980s, a group of researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine set out to better understand the aging brain by recruiting almost 500 men and women ages 75 to 85 living in the Bronx. Each person underwent neuropsychological tests and responded to questionnaires about their health and lifestyle. Then, over the next couple of decades, the researchers tracked the people’s cognition.

“Perhaps not surprisingly, the scientists found that, for every cognitively challenging activity performed one day a week, there was an associated 7 percent reduction in dementia risk. The more often people tested their brains — such as with board games or crossword puzzles — the less likely they were to develop Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia.

“But when it came to physical activity, one hobby stood out above the others after controlling for other lifestyle and health factors: dancing.

“The researchers, who published their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2003, concluded that physical activities such as swimming and walking also trended in the right direction but that their results were not as profound as those associated with dancing. …

“Physical activity, especially aerobic exercise, in general is wonderful for our brain health. And this isn’t intended to knock walking. … But combining physical activity with creativity and cognitive challenges may help protect the brain further. Dancing asks your brain to do several things at once: match a rhythm, remember steps (or quickly improvise some new ones), navigate space and perhaps even respond to a partner. …

“Dancing is simply music-based movement — ideally of a kind that makes you feel good and involves the company of others. And it can truly be for almost everyone. In my own clinic, we recommend dancing as therapy for patients with movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease. …

“Besides brain health, there are other great reasons to consider shaking a hip. A 2020 meta-analysis of 29 randomized trials among healthy older adults found that social dance-based activities were associated with a 37 percent reduced risk of falling — as well as improvements in balance and lower body strength. …

“While many community centers offer dance classes specifically for older adults (often free), I know that dance classes suited to your interests and needs are not always easily available nearby. … There are also several classes on YouTube tailored to possible physical limitations and needs. …

“Even if you’re not up for dancing, there’s still power in playing your favorite tunes: A large population study published recently found that just listening to music most days was linked to a decrease in dementia risk.

“Music can evoke memory and emotions, but certain kinds of it can also offer a distinctly enjoyable challenge to the brain. As you listen to music, your brain is constantly evaluating its predictions regarding what comes next: Will the next note and beat be the one you’re anticipating?

“A potent driver of the urge to groove is syncopation. When music is syncopated — meaning, you expect to hear a loud beat in line with the rhythm, but instead it’s weak, or there’s a quick pulse of silence — it challenges our brain’s expectations. Think ‘Satisfaction’ by the Rolling Stones or ‘Uptown Funk’ by Bruno Mars.

“Syncopation creates an exciting sense of ‘push and pull in the music. Humans perceive songs with a healthy dose of syncopations as more pleasurable. Studies have found that those syncopations strongly compel us to bust a move, completing that gap our brain is craving to fill.

“There’s no magic bullet to prevent dementia. Cognitive changes are the result of several factors converging in our brains — our genetics, lifestyle, stress, diets and environmental exposures. Walking and other forms of physical activity can help boost your brain health, but doing so shouldn’t feel like a chore. Cognitive strength can also grow out of many activities that give us great joy — moving to music you truly love, sharing space with someone else’s company, and trying something new without worrying how you look doing it.”

More at the Post.