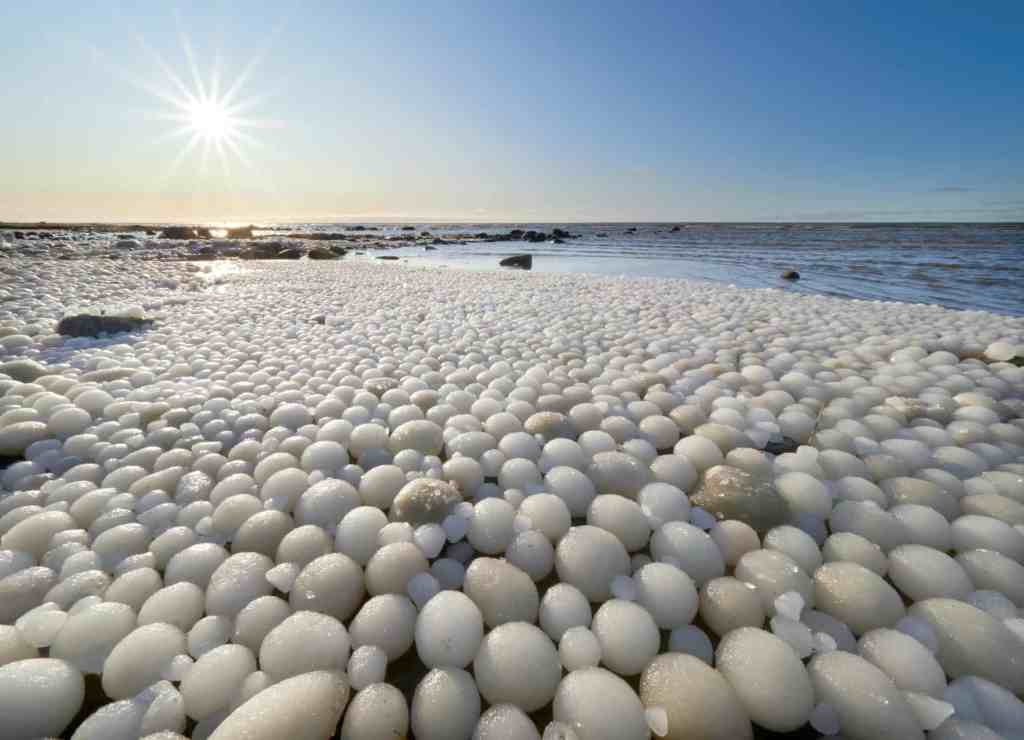

Photo: Peace Tracks.

Sandra Rizkallah and Tom Pugh, founders of Plugged In Band and Peace Tracks, at a 2024 United Nations event for the International Day of Education.

We used to say in the sixties that education should get the mega funding and the Defense Department hold a bake sale, instead of the other way around. (Humor paper the Onion gets the idea here.) Nothing has changed. The worthy cause described below has been defunded by our government and is now looking for alternate benefactors.

James Sullivan had the story for the Boston Globe. It’s about a Massachusetts peace group that makes music with teens from war-torn countries.

“Tensions are running high across the globe, but the couple behind the Needham-based initiative Peace Tracks are doing what they can to alleviate some of that through collaborative songwriting workshops. Launched during the pandemic, Peace Tracks is an offshoot of Sandra Rizkallah and Tom Pugh’s nonprofit Plugged In Band, which has been connecting students who want to form rock bands for 24 years.

“After a harrowing hospitalization with COVID in 2021, Rizkallah went home to recuperate.

” ‘It was a time for me to dream, to play, to do something I always wanted to do,’ she said. That’s when the couple came up with the idea for Peace Tracks.

“The new program focuses on teenagers living in conflict-torn regions, including Ukraine, Palestine, Lebanon, and refugee camps in Jordan and Berlin. Interacting online with the help of Peace Tracks facilitators, the students learn to practice empathy and compassion while writing and recording music together.

Peace Tracks was recently named one of the world’s 100 ‘brightest education innovations’ by the Finland-based HundrED Foundation.

“Working with students from around the world ‘forces you to get out of your bubble and think about bigger problems,’ said [Ali Belamou, a 16-year-old who lives in Morocco]. ‘The conversations are deep, personal, and intimate.’

“His classmate, Ismail Sebai, said he has learned English as a second language primarily through music and movies. He counts Brent Faiyaz, Bryson Tiller, and Drake among his favorite rappers. …

“Joining the students on the call was Afifa el Bassim, their English instructor. … With the Peace Tracks program, ‘we give them the freedom to say what they want,’ she said of the students. …

” ‘Another educator on the call, Gideon Gichiri, has been working with the Peace Tracks program in a refugee community in Berlin. A native of Kenya, he moved to Germany in 2022. After meeting Rizkallah and Pugh when they were visiting Berlin, he introduced the group’s work to the Sprach Café, a space for immigrants to learn German.

“Music, he said, truly is a universal language. ‘When the world is very fast, music slows it down,’ he said.

“Luke Flinter is an aspiring rock musician growing up in Falls Church, Va. He said that each Peace Tracks participant contributes what they can to the songwriting process. Some who have musical skills may cut instrumental tracks for their fellow students to write to. In some cases, he said, ‘I would edit their guitar parts or re-record what they did.’

“Others in these small groups — typically four to eight teammates, plus facilitators — might use their phones to record footage for videos.

“Flinter spent some of his young life in Abu Dhabi, before his family settled outside of Washington, D.C. Peace Tracks, he said, ‘proves what I already thought: that music transcends every cultural and racial boundary.’

“Rizkallah has always felt compelled to seek antidotes to world conflict, she said. Her mother was a Holocaust refugee who instilled in her ‘not a sense of being a victim, but more a humanitarian. My mom was always helping people, regardless of who they were or where they came from.’

“Peace Tracks launched in late 2023 with students from the US, Jordan, Morocco, and Palestine. One week later, the war in Gaza began.

“ ‘It’s been moving for all of us to see how the program has positively impacted everyone,’ Rizkallah said, ‘but especially the youth in Palestine. They felt unheard.’

“ ‘Peace Tracks gave me hope,’ said Faris, a Palestinian student from Ramallah who wants to study international relations, in an email. ‘I saw students from many countries working toward one goal. … ‘That experience showed me that people who care still exist.’

“Until June, Peace Tracks was funded by a two-year US State Department grant. … The group is currently working to develop fund-raising through other resources.

“In September, Rizkallah and Pugh traveled to the United Nations General Assembly in New York City, where they attended a discussion about ‘leading in messy times,’ Rizkallah explained. Among other things, she learned that sometimes it’s better to plunge into your project and set your course as you go. ‘You don’t have to have everything figured out,’ she said. ‘You might have to do it messy. That really had a deep impact on me. … ‘It’s been challenging, [but we] wholeheartedly believe in this mission.’ ”

More at the Globe, here.