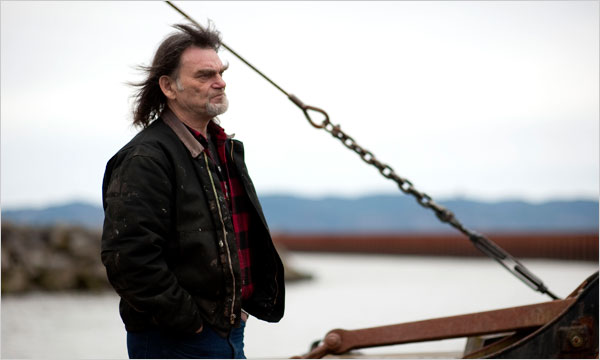

Photo: Shimabuku.

Unlike animals that spend their days eating, sleeping or mating, octopuses “have time to wander — time for hobbies,” says Shimabuku, who makes art for sea creatures to enjoy.

There’s an artist in Japan who makes art for marine animals just to see how they react. The responses of octopuses seem to be the most gratifying to him. The whole time I was reading this story, I was wondering why I had never heard the naturalist Sy Montgomery, author of The Soul of an Octopus, talk about this on Boston Public Radio in one of her her weekly visits. I must have missed that day.

“When the Japanese artist Shimabuku was 31 years old,” writes Francesca Perry at CNN, “he took an octopus on a tour of Tokyo. After catching it from the sea with the help of a local fisherman in Akashi, a coastal city over 3 hours away from the Japanese capital by train, he transported the live creature in a temperature-controlled tank of seawater to show it the sights of Tokyo before returning it safely to its home the same day.

“ ‘I thought it would be nice,’ the artist, now 56, said about the experience, over a video call from his home in Naha, Japan. …

‘I wanted to take an octopus on a trip, but not to be eaten.’

“Documenting it on video, Shimabuku took the octopus to see the Tokyo Tower, before visiting the Tsukiji fish market, where the animal ‘reacted very strongly’ to seeing other octopuses on sale, the artist said. …

“The interspecies day trip, resulting in the 2000 video work ‘Then, I Decided to Give a Tour of Tokyo to the Octopus from Akashi,’ kickstarted a series of projects Shimabuku has undertaken over the decades that engage with octopuses in playful, inquisitive ways. A portion of this work is currently on show in the UK, in two exhibitions that explore humanity’s relationship with nature and animal life: ‘More than Human‘ at the Design Museum in London (through October 5) and ‘Sea Inside‘ at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich (through October 26).

“Fascinated by what the sea creatures might think, feel, or like, Shimabuku has documented their reactions to various experiences, from the city tour of Tokyo to being given specially crafted artworks. ‘They have a curiosity,’ he said. …

“When he lived in the Japanese city of Kobe, Shimabuku would go on fishing trips with local fisherman, taking the opportunity to learn about octopuses. ‘Traditionally we catch octopuses in empty ceramic pots — that’s my hometown custom,’ he said. Fishermen would throw hundreds of pots into the sea, wait two days, then retrieve them — finding octopuses inside. ‘Octopuses like narrow spaces so they just come into it,’ explained Shimabuku.

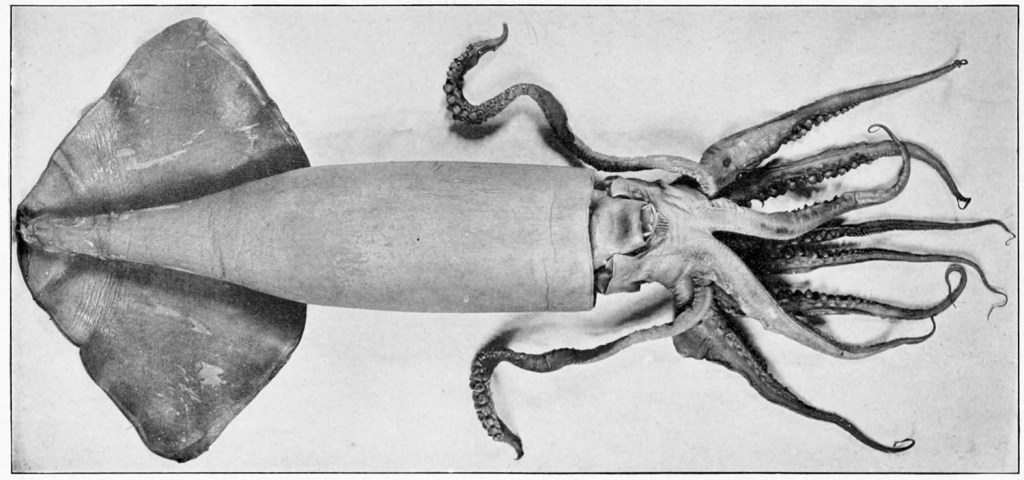

“When he saw the animals within the pots, he discovered they were ‘carrying things’: shells, stones, even bits of broken beer bottles. He began to save the small objects the octopuses had gathered. …

“Shimabuku started to think, ‘maybe I can make sculptures for them.’ … In his 2010 work ‘Sculpture for Octopuses: Exploring for Their Favorite Colors,’ Shimabuku crafted a selection of small glass balls and vessels, in various colors. At first, he went out in a fishing boat and threw the sculptures in the sea, ‘like a present to the octopuses.’ But then he wanted to see how the animals were reacting to the objects.

“Collaborating with the now-closed Suma Aqualife Park in Kobe, he repeated the effort in a large water tank, where he could film the reaction of octopuses.

“ ‘They played with them, and sometimes they carried them,’ said Shimabuku. … ‘They keep touching, touching.’ The resulting film, and photographs, show the octopuses wrapping their tentacles around some of the glass objects, grabbing and rolling them across the sand, and even holding them in their suckers as they move across the side of the tank.

“In 2024, Shimabuku had a landmark solo show at Centro Botín in Santander, Spain. Specially for the exhibition, he collected an assortment of glass and ceramic pots to offer to local octopuses. Some of the vessels were made by the artist and others were from ‘second-hand shops and eBay.’ …

“Although octopuses are colorblind, Shimabuku wanted to see through these projects whether they were attracted to objects of certain colors. ‘What I heard from fishermen is that octopuses like red,’ he said. ‘Long ago in Kobe, I found an octopus in a red pot, so I believe they like red.’ Perhaps more so than the hue, Shimabuku is convinced that octopuses are drawn to very ‘smooth, shiny’ glass objects. He doesn’t have evidence to back this up, [he’s just] a man entranced by eight-legged mollusks is dedicating his time to engaging with them through art.”

More at CNN, here.