Photo: Sayuri Suzuki/GKIDS.

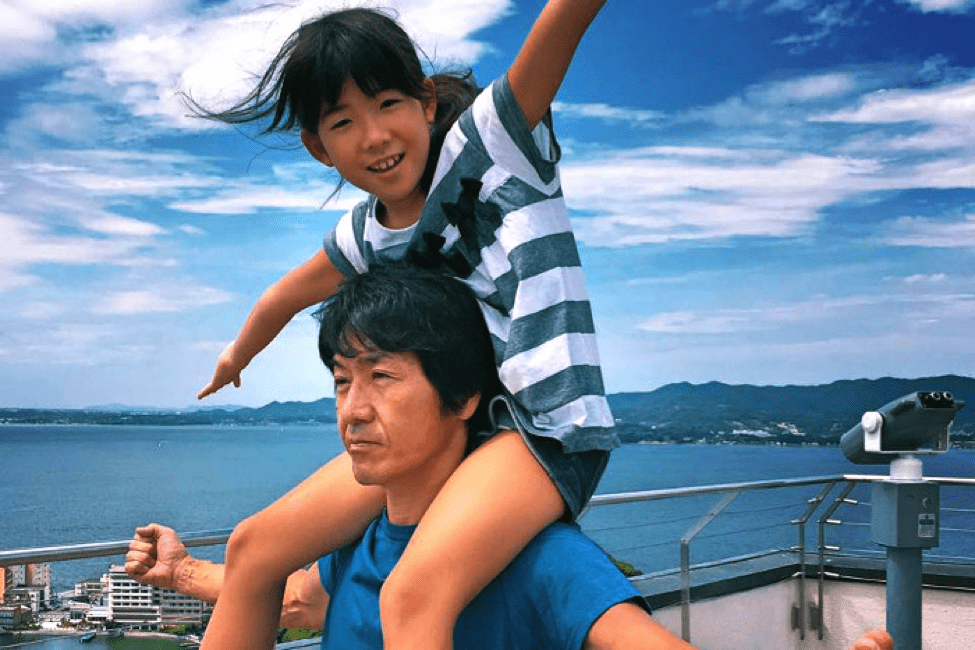

Ryo Yoshizawa and Ryusei Yokohama as Kikuo and Shunsuke, rival kabuki actors in Japanese Oscar submission Kokuho.

A popular new movie is reviving interest in an ancient Japanese art form, and those who know how to practice it are wondering how that will affect their future.

Thomas Page reports at CNN, “In the movie Kokuho, a three-hour epic spanning half a century in the life of a fictional kabuki actor, we see the traditional art form slowly retreat from Japanese popular culture. What was once a national interest — albeit, a relatively middle class one — recedes into a niche, performed by an aging cohort artistically frozen in time.

“In art, so in life. Kabuki is struggling in Japan. The 400-year-old UNESCO-inscribed classical theater is battling to attract an audience. Data shared by the Japan Arts Council shows attendance at National Theatre venues has dropped significantly, and has not returned to pre-pandemic levels.

“Kabuki is also failing to attract apprentices, the de facto route for pursuing a career in the art. Historically, acting dynasties have produced a healthy stable of performers, but in recent decades the state has picked up the slack. Courses at the National Theatre Training School have trained a third of kabuki performers working today, but the school received just two applicants for its latest two-year acting course.

“Enter Kokuho. Based on Shuichi Yoshida’s bestselling novel of the same name, the movie, directed by Lee Sang-il (Pachinko) and starring Ryo Yoshizawa, has captivated audiences after debuting at the Cannes Film Festival in May. …

“The film has been the talk of the town among Tokyo’s kabuki performers, according to local reports. But more than that, it could be drawing people to the performing art. …

“When kabuki performer Nakamura Ganjiro IV (who appears in the film and also instructed other actors on their performance) made an appearance at the National Theatre alongside director Lee in September, 2,200 people applied for 100 seats, said the [Japan] Arts Council.

“Looking to seize the moment, the Arts Council has distributed flyers for its January 2026 program outside cinemas showing the film, launched a tie-in social media campaign, and put on introductory performances of kabuki masterpieces with more affordable seating to encourage newcomers. …

“Kokuho translates as ‘national treasure,’ a reference to ‘ningen kokuhō,’ or ‘living national treasure,’ a title designated to masters of their art.

“The film opens in the 1960s and follows the orphaned son of a yakuza boss, Kikuo, on his journey into the upper echelons of kabuki. At age 15, he’s old for an apprentice … though he has the tutelage of Ken Watanabe’s seasoned pro Hanjiro, and the competition of Hanjiro’s son Shunsuke (Ryusei Yokohama) spurring him on.

“Kikuo performs as an ‘onnagata’— a male actor specializing in female roles — a custom that began in the 17th century. That comes with its own dictates, including posture, walk and dance moves. …

“ ‘The more I did the dancing, the more I saw how difficult it was going to be to reach the level of actual kabuki actors,’ [the actor said]. …

“In the movie, Kikuo’s smooth ascent from outsider to stardom is tempered by his affairs and the jealousy he inspires in others. But these points of friction rarely eclipse the heightened drama on stage.

“The screenplay draws on kabuki’s established repertoire, featuring stories of love rivalries, transfiguration and suicide, often deployed to parallel character narratives and reflect their inner state. Kokuho provides helpful on-screen synopses for the uninitiated. …

“The director and cast had to negotiate the pitfalls of shooting stage acting for screen; crafting performances made to be seen by the cheap seats in a back of a kabuki theater, captured by the close-up camerawork of cinematographer Sofian El Fani. …

“ ‘I was told by Director Lee that this wasn’t about doing a beautiful dance on stage, but really showing who Kikuo is as he’s performing,’ said Yoshizawa. “Focusing on things like a trembling finger in a certain moment to show his mental situation, to really concentrate his whole life and show that on stage.’ …

“The epic concludes in 2014, with Yoshizawa aged up and Kikuo forced to confront the damage and hurt he has caused on his path to greatness.

“For the actor, it was not the usual case of playing old. ‘There’s a difference between a person who plays the onnagata in kabuki growing old, versus a regular man growing old,’ he explained. ‘I noticed in the reference material they would stay young and beautiful … I’d seen they keep their great posture.’ ”

More at CNN, here.