Above: At the former Loring Air Force base in Maine, there are hopes that a planned data center will use less water for cooling equipment by using a technique that submerges computer components in a nonconductive, oil-based fluid to draw heat directly from the source.

The rapid increase of energy-guzzling buildings for artificial intelligence has people talking about better ways to cool the systems. One idea is to build them in somewhere off Planet Earth, which sounds like a horrible idea to me. Meanwhile in Maine, developers are investigating a different approach.

Ryan Krugman writes at Inside Climate News, “Once a Cold War outpost near Maine’s northern border, the former Loring Air Force Base could soon be home to a very different kind of facility: the state’s first large-scale data center. The sprawling 450-acre site in Limestone, Maine, would host the giant server farm as part of a plan still in its early stages to reinvent part of the base as a hub for green technology.

“Since its closure in the early 1990s, the Loring Development Authority has redeveloped the base into a business park and a commercial airport. More recently, it has also become a sustainability-focused campus through the company Green 4 Maine.

“Developers say Loring’s fiber network and access to renewable hydropower make it an ideal site for a next-generation data center powered entirely by green energy and using water-free cooling technology. But questions remain over how such an energy-intensive project could impact utility rates, grid reliability and a sensitive surrounding environment.

“Traditionally, data centers, among the most power-hungry and resource-dependent buildings in the world, rely on massive cooling systems to keep thousands of servers from overheating. Some use energy-intensive fans that circulate air through vast server halls, while others depend on large volumes of water to absorb heat. ‘I wake up every morning wondering why we still use air to try and cool electronics,’ said Herb Zien, vice chair of LiquidCool Solutions, one of the developers of LiquidCool Data Center. ‘As a thermodynamics engineer, I used to use air to insulate, not cool.’

LiquidCool Solutions, a privately held company based in Rochester, Minnesota, takes a different approach to cooling electronic technology.

“Its ‘immersion cooling’ technology, Zien said, submerges computer components in a nonconductive, oil-based fluid that draws heat directly from the source — eliminating the need for fans, air conditioning or water. The system produces no toxic byproducts or emissions and, according to the company, nearly eliminates both noise and evaporative loss. Loring, company officials say, will serve as the first large-scale data center built entirely around its technology—its first real-world test. …

“The developers say [the data center] will be entirely powered by renewable energy—mainly hydroelectricity. [But] Versant Power, the region’s transmission and delivery utility, wrote in an email that … it could not verify that the supply would come from hydro or renewable sources. The utility added that grid upgrades would likely be necessary to support the project — costs that would be covered by the developers.

“A Harvard Law School Environmental and Energy Law Program study found that, while initial costs are paid for by the developers, data center projects often shift expenses onto ratepayers through discounted or tailored negotiated contracts, wholesale market charges and grid upgrades that may exceed what’s necessary for reliability.

” ‘Adding 50 megawatts to such a small, isolated grid is huge,’ said Hepeng Li, an assistant professor at the University of Maine’s College of Engineering and Computing. Northern Maine’s independent grid has a peak load of roughly 150 megawatts, meaning the data center alone could consume more than a third of the region’s total demand.

“Nearly 50 megawatts of mostly hydroelectric power — currently supplied by New Brunswick Power — is available at a nearby substation, according to Zien. New Brunswick Power told Inside Climate News that no supply agreement or memorandum of understanding is in place with either Green 4 Maine or the Loring Data Center project. …

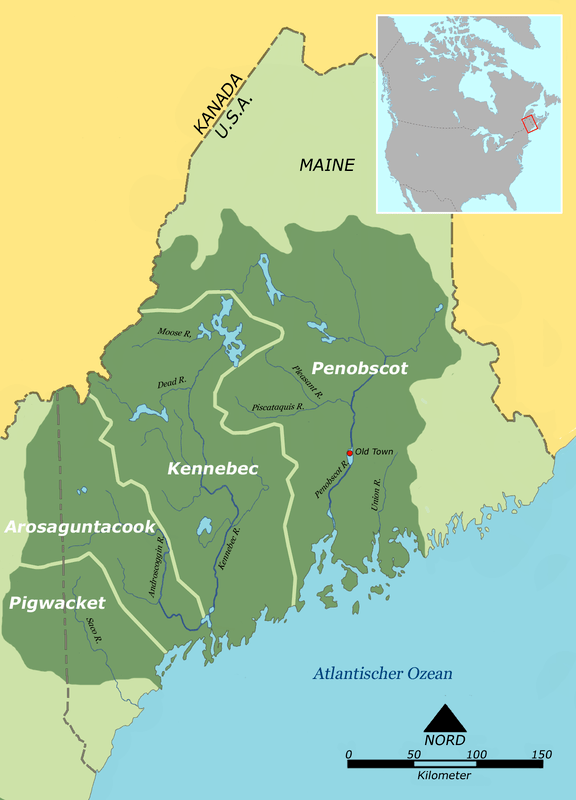

“Developers also plan to install on-site diesel generators to provide backup power during grid outages. While standard for data centers, a diesel backup system can emit harmful air pollutants — including particulate matter, volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides — posing potential risks to the Mi’kmaq Nation and the Aroostook National Wildlife Refuge, which border the site. …

“Project officials say generators would not be installed immediately and that some future users might choose to operate without them. …

“Those uncertainties would only grow if the project succeeds and the developers expand the data center beyond its initial 2- to 6-megawatt capacity. Even so, supporters and researchers say that if the cooling technology performs as promised and the developers can secure a reliable supply of Canadian hydropower, the project has the potential to chart a new direction for cleaner, water-free data center development.”

More at Inside Climate News, here. I admire inventors who come up with useful ideas. But I don’t know about this one. When there is money to be made, inventors often seem too sanguine about how well things will work. Imagineering combined with practicality is a consummation devoutly to be wished.