Summer is coming, and all over America, kids will be seeking out basketball hoops for pickup games or organized sports. Today we know that the recognized stars of the game are often Black, but apparently, that wasn’t always the case.

Frederic J. Frommer explains at the Washington Post why Edwin Bancroft Henderson is “known as the ‘father of Black basketball’ (or sometimes the ‘grandfather’). The first Black certified instructor of physical education in the United States, [he] brought the White-dominated sport to Black America. …

“ ‘Henderson and his contemporaries envisioned basketball — and sports in general — as providing a rare opportunity to combat Jim Crow,’ wrote Bob Kuska in Hot Potato: How Washington and New York Gave Birth to Black Basketball and Changed America’s Game Forever.

“[Henderson] learned basketball while studying physical education at Harvard University’s Dudley Sargent School of Physical Training. The school was affiliated with the International YMCA Training School in Springfield, Mass., where James Naismith had invented the sport just a decade earlier. When Henderson returned to Washington, he organized a basketball league for Black players, in a city where only Whites had access to basketball courts or clubs.

“ ‘What’s sad is that more people don’t know the story of E.B. Henderson, who was a pioneer, a trailblazer, someone who was a direct protégé of Dr. Naismith,’ said John Thompson III, the former head men’s basketball coach at Georgetown University, now vice president of player engagement at Monumental Basketball.

“Today, community leaders are taking steps to raise Henderson’s profile. In February, the University of the District of Columbia renamed its athletic complex the Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson Sports Complex. The school also launched the Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson Memorial Fund, which will help pay for the renaming, a scholarship endowment and the creation of a permanent Henderson memorial on campus. …

“On April 1, the Wizards named forward Anthony Gillthe inaugural winner of the team’s E.B. Henderson Award, which recognizes the Wizards player most philanthropically active in the D.C. community.

“And last year, Virginia honored Henderson with a state historical marker in Falls Church, where he lived from 1910 to 1965 and helped organize the NAACP’s first rural branch. Henderson also served as president of the Virginia NAACP.

After completing his studies at Harvard, Henderson tried to attend a basketball game at a Whites-only YMCA in D.C. in 1907 along with his future brother-in-law, but they were shown the door by the athletic director.

“Undeterred, Henderson started the D.C.-based Basket Ball League, where his 12th Street YMCA team went undefeated in 1909-10 in competition with local rivals and teams from other cities and won the unofficial title of Colored Basketball World Champions.

“His playing days came to an end in 1910 when he was 27 [but] Henderson’s work continued off the court, as he formed the Public Schools Athletic League, the country’s first public school sports league for Black students, which included basketball, track and field, soccer and baseball.

“In 1912, Henderson moved to Falls Church, and soon he was taking on racial discrimination there, helping to challenge a local ordinance that restricted where Black residents could live. After a court ruled the ordinance unconstitutional, the Town Council rescinded it.

“Henderson continued to challenge discriminatory treatment of African Americans, often through the many newspaper articles and letters to the editor he wrote over the years. In a September 1936 letter to the Post titled ‘The Negro in Sports,’ for example, he touted the success of Black athletes such as track star Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

“ ‘Right here in Washington, it ought to be possible for a Jesse Owens, or a city-wide marble champion, or a Joe Louis to come up through the lists and tournaments,’ he wrote. ‘When will the Capital of the Nation meet this challenge?’

“In 1939, he wrote a book with the same title, The Negro in Sports, which he updated in 1950. In the intervening decade, Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color barrier, and Black players had returned to the NFL after being shut out of the league for a dozen years.

“ ‘Henderson resists what might have been the high temptation to gloat at the sensational success of the Negro boys when finally they got their chance to play in the big leagues,’ Shirley Povich wrote in a Washington Post review of the revised edition. ‘Instead, he pays tribute to the American sportsmanship that sufficed, finally, to provide equal opportunity.’ …

“ ‘I never consciously did anything to be first. I just happened to be on the spot and lived in those days when few people were doing the things I was doing,’ Henderson said a few years before his death in 1977, at the age of 93. ‘But sports was my vehicle. I always claimed sports ranked with music and the theater as a medium for recognition of the colored people, as we termed ourselves in my day. I think the most encouraging thing, living down here in Alabama, is to see how the Black athlete has been integrated in the South.’

“Henderson was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2013, following a campaign waged by his grandson, Edwin B. Henderson II, a retired educator and local historian.”

More at the Post, here.

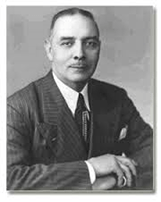

Photo: University of the District of Columbia.

Edwin Bancroft Henderson, the “Father of Black Basketball.”