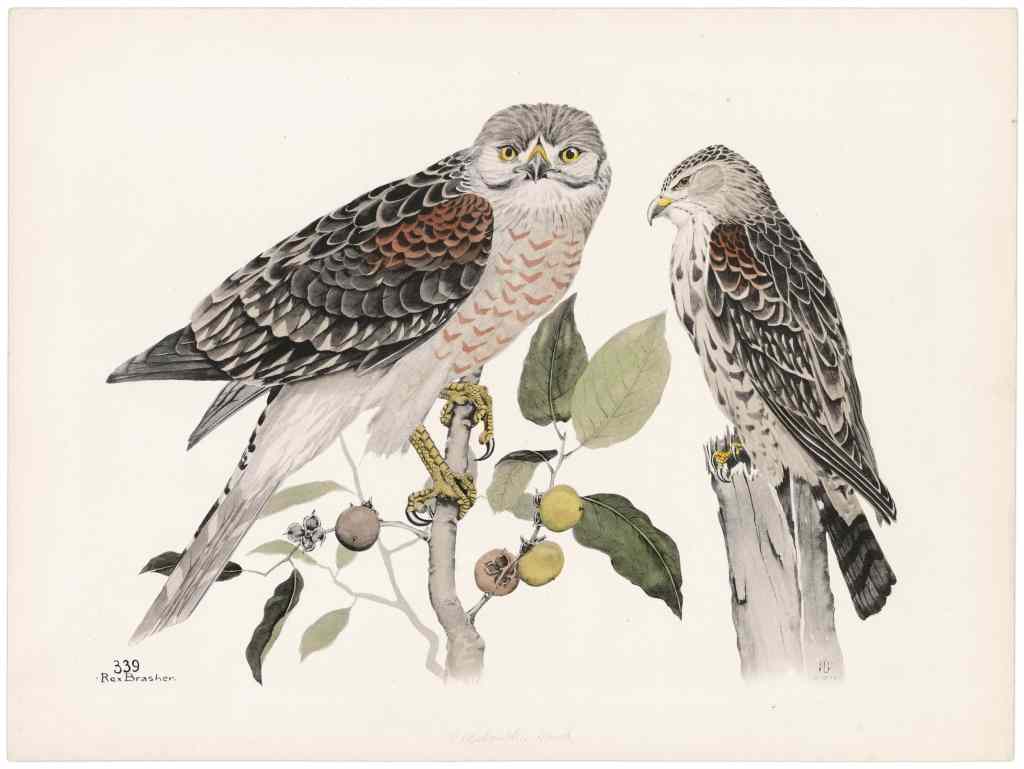

Art: Rex Brasher.

Rex Brasher painted more birds than Audubon — and never owned slaves.

With the more widespread understanding that bird painter John James Audubon owned slaves, controversy about honoring his name has erupted. Although for now the National Audubon Society is still the National Audubon Society, carrying on its otherwise great work, a small group called the Rex Brasher Association is advocating for more attention to another prolific bird painter of roughly the same period, Rex Brasher.

Philip Kennicott writes at the Washington Post, “On a gray day in March, Rex Brasher’s place looks a bit forlorn. The farmhouse is empty and the little shop made of cinder blocks feels derelict. But the leaders of the Rex Brasher Association who have gathered to show off the place see only possibilities for the 116-acre property.

“They want to place this wooded patch of the Taconic Range into conservancy, add modern studios for artist and naturalist residencies, refurbish the main house and cottage, and build a small museum inside the old shop. Two years after the death of the last Brasher relative to live on-site, they hope to resurrect the legacy and reputation of a man many people feel painted birds as well as or better than John James Audubon.

“Born in 1869, Brasher left an enormous body of paintings, almost 900 large-scale watercolors documenting American bird life and habitat, that became the source material for a monumental 12-volume compendium of hand-colored reproductions published as Birds & Trees of North America. He also made an unknown number of miscellaneous paintings and drawings, wrote a delightfully eccentric volume of philosophical reflections called Secrets of the Friendly Woods, and penned a hand-illustrated autobiographical account of his early forays, by sailboat, to document waterfowl from New England to Florida.

“Brasher was a retiring artist — a modest man who lived much of his life off the grid — which may be one reason he isn’t more famous. But his life’s project to document American birds, an effort to outdo Audubon that began in the 1890s and continued into the 1920s, was celebrated in its day, with an exhibition at the Explorers Hall of the National Geographic Society in 1938. Later, when he began hand-coloring more than 87,000 individual plates for publication, the project attracted subscriptions from collectors and patrons, as well as universities and libraries. Today, a complete set of his printed work can fetch more than $40,000.

“He was praised by naturalists including John Burroughs (‘he is the greatest bird painter of all time’) and T. Gilbert Pearson, who helped found the organization that would ultimately become the National Audubon Society.

‘When you see a Brasher bird, you have seen the bird itself, lifelike and in a natural attitude.’

“But Brasher was very much a man of the 19th century, and despite periodic efforts to revive his work, his legacy — closely observed, naturalistic renderings of animal life — still suffers from having been out of step with the avant-garde and experimental art of the 20th century.

“That could change, however. The Connecticut State Museum of Natural History, which owns some 800 of the original watercolors, is planning to make them more accessible to the public with exhibitions in a new building, for which they will shortly begin fundraising. The efforts of the Rex Brasher Association, which has taken stewardship of the Upstate New York property near Kent, Conn., where Brasher lived until the mid 1940s, include digitizing and publicizing his work. And cultural changes, including a broader sense of what qualifies as fine art and a new urgency about the fragility of the natural world, may make people today more sympathetic to rediscovering his legacy.

“Brasher may also benefit from growing awareness that Audubon, to whom he was often compared, was a complicated, often odious figure, whose interest in birds grew out of a raw will to power more than any particular love of the species. Audubon was a formidable artist but also a ferocious antagonist within what Audubon scholar Gregory Nobles calls the ‘ornithological wars of the 1830s.’ He was also an enslaver and deeply contemptuous of the abolitionist movement in both the United States and the United Kingdom, where he spent considerable time preparing his landmark publication, The Birds of America, published between 1827 and 1838. The National Audubon Society is in turmoil today as local chapters drop the Audubon name and board members resign because the national leadership refuses to do so.

“Audubon studied birds in the wild before shooting them and then staging their carcasses in lifelike poses, a work process that has also aroused criticism even though it was standard practice for naturalists to kill animals they sought to collect and preserve. Those collections remain scientifically invaluable. …

“Audubon’s original paintings are a marvel, especially when seen up close. They are marvelously detailed and dramatic, and Audubon was particularly alert to the iridescent quality of feathers, which he reproduced with layers of silvery graphite over the pigments. But these images are also stagy and contrived, as if his birds are players on a stage, dramatically illuminated in the glow of gaslight. …

“Brasher sought a more naturalistic treatment, without Audubon’s operatic drama. Although he hunted and collected birds as a young man, he gave up that approach later, preferring close observation to specimen hunting. His paintings have a lightness and transparency wholly different from Audubon’s heightened atmosphere. He also had access to museums with extensive specimen collections and the published work of predecessors. He painted over 1,200 species of birds, far more than Audubon’s 497, but he was also building on the legacy of Audubon and others. …

“Between the early days of the artist-woodsman ornithologists and the death of Brasher a century and a half later, the science of ornithology spun off a vital and flourishing adjunct: birdwatching. Brasher might be considered the patron saint of that project. He was keenly interested in making accurate images of birds, but he was also interested in learning from birds. In Secrets of the Friendly Woods, he wrote about nature with a mix of genial animism and psychological insight. Nature was inexhaustible for him: ‘Forty years have not diminished the hope that each time afield I shall see something new, learn a novel habit of a bird or animal, and that expectation is seldom disappointed.’ …

“The difference between the artists’ work is like the difference between a grand aristocratic portrait and a psychologically nuanced character sketch. Audubon gets the dress and regalia right, and his birds project a powerful, self-fashioning sense of their own presence and importance. Brasher’s birds live contentedly in their own world and don’t need to perform or impress the viewer. If Brasher sometimes tends to moralize when he writes about birds, it isn’t Aesopian. The moral is almost always the same: We could learn a lot from birds.”

More at the Post, here.