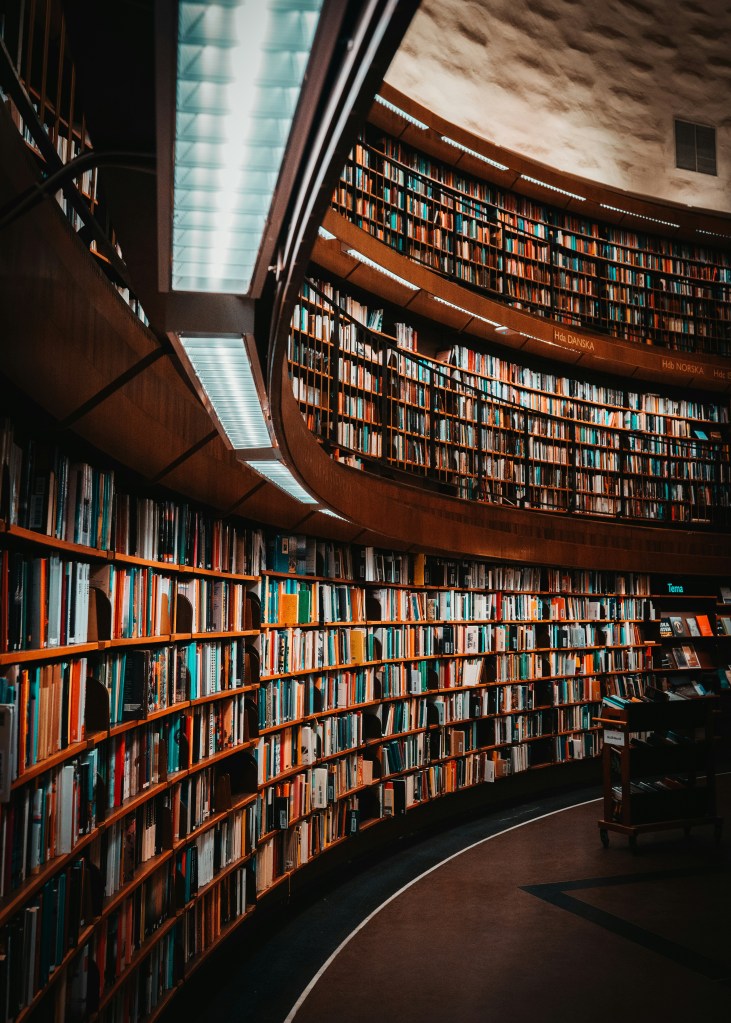

Photo: Emil Widlund/Unsplash.

Funny how quiet, unassuming institutions like libraries keep getting in the news! Today’s story is one example. But it’s not about libraries as sanctuaries during riots or about mild-mannered librarians standing up to book banning. It’s about the way libraries run themselves and how companies could learn something from them.

Criag Shapiro writes at Fast Company, “Walk into a library and you’ll feel it right away. It’s quiet but alive. People are reading, learning, applying for jobs, finding shelter, escaping for a moment into a story. No one’s selling anything. Yet the value being created is enormous.

“In 2022 (the most recent year for which we have data), there were 671 million visits to public libraries in the United States. … Despite changes in media habits, younger generations use libraries more than any other cohort (54% of Gen Zers and millennials in the U.S. reported visiting a physical library in the past year). And that’s not counting the millions more who use the myriad digital services public libraries offer. …

“We’re living in a time of rapid change. Trust in institutions is slipping. … AI is transforming the nature of work. Economic pressure is rising for employees, founders, and leaders alike. Against that backdrop, it’s tempting to think only in terms of efficiency, cost-cutting, and optimization.

“But there’s a deeper opportunity. What if long-term success is more about building environments where people feel inspired, curious, and connected? That’s what libraries do. And that’s what the best organizations of any kind are learning to do, too.

“Libraries don’t ask you to justify your interests. You can check out a book on astrophysics or attend a poetry reading. No one’s measuring your productivity. The door is open, and the invitation is simple: Explore.

“Great companies operate with a similar principle. They give people space to think. To chase ideas that might not have an immediate return. Not because it’s soft or unfocused, but because it leads to better breakthroughs.

“On the way to becoming a company worth more than $2 trillion, Google famously gave employees ‘20% time,’ encouraging them to pursue passion projects without immediate commercial goals. This freedom led directly to innovations like Gmail, Google Maps, and AdSense. …

“A library is not about monetization. Yet its value shows up everywhere: literacy rates, employment readiness, civic health. The best organizations understand this. They offer more than a product. …

“Patagonia demonstrates this principle powerfully through its environmental activism, which goes far beyond selling outdoor gear. The company’s bold stances — from suing the government over environmental policies to donating profits to climate causes — might seem risky from a traditional business perspective. Yet Patagonia’s sales have quadrupled in the past decade to more than $1 billion annually. Patagonia’s commitment to meaning over pure profit resonates deeply with its community, strengthening brand loyalty and trust. …

“Libraries recognize that people are more than readers or borrowers. They offer after-school programs for children, job training for adults, and social services for those in need. They understand visitors have complex lives, and that growth rarely follows a single, predictable path.

“The best organizations understand this, too. Work is not just work. It’s identity. It’s purpose. It’s how people spend the majority of their waking hours. When leaders recognize that … people stay longer. They perform better. They build things they’re proud of. …

“Healthy people build healthy organizations. The modern library is more than books. It hosts résumé workshops. Offers tax help. Provides warmth in the winter. It meets people where they are. That’s a powerful concept for any organization.

“Consider Airbnb. What began as a way to find short-term lodging is steadily evolving into something broader: a platform for travel, connection, and cultural exchange. Now the company is expanding from where you stay to how you explore, offering everything from pasta-making in Rome to wildlife walks in Nairobi. It’s a bold attempt to transform a transactional service into a layered, participatory ecosystem that reflects the ways travelers want to feel at home in the world.

“What if you stopped thinking of your offering as a single product or service? What if you thought of it as a foundation people could build from?

“Libraries remind us that value isn’t always immediate or measurable in quarterly reports. But it’s real. The impact accumulates over time, quietly compounding. The same can be true for any organization willing to think more expansively.

“Invest in culture. Make room for imagination. Support your people. Serve your community. Not because it looks good, but because it works.” More at Fast Company, here.

At this moment of pervasive anxiety in the US, I’m not sure businesses or employees can relax enough to experiment with being like libraries and librarians. What do you think? Is the analogy a stretch?

Photo: Helen H. Richardson/Denver Post

Photo: Helen H. Richardson/Denver Post