Photo: Danielle Khan Da Silva.

Divers risk their lives to protect whales from “ghost nets” abandoned by fishermen.

Today’s article presents one of those impossible challenges pitting the environment against the need to make a living. In this case, it involves the ocean, specifically marine animals.

Danielle Khan da Silva has the story at the Guardian.

“After a day of scuba diving, Luis Antonio ‘Toño’ Lloreda was exhausted. Then a friend brought urgent news. ‘Toño, man, there’s a whale caught in a net out there.’ Lloreda, 43, had freed other, smaller wildlife from fishing nets but this would be his first marine animal of such size.

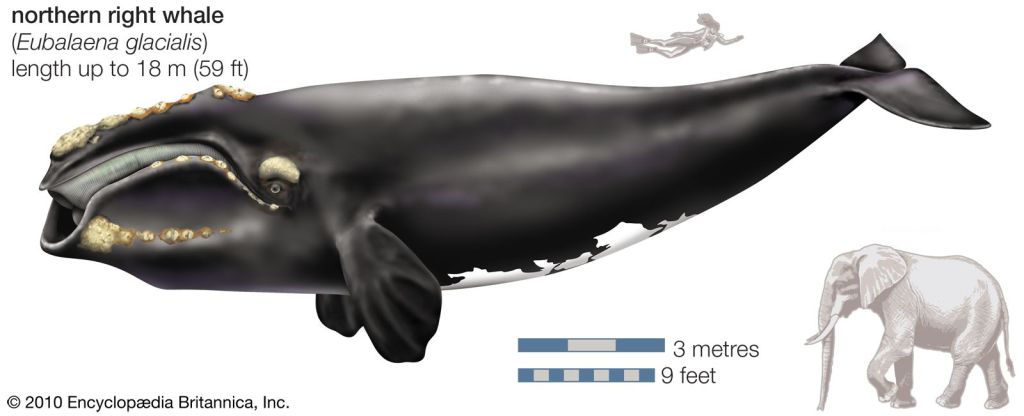

“The four- to five-meters-long juvenile humpback, accompanied by its mother, had a net studded with hooks wrapped around its fin and mouth. One wrong move could have been fatal for Lloreda or the whale.

‘To connect with the whale, I used what we call intuitive interspecies communication,’ says Lloreda, explaining that this involves non-verbal, energetic communication.

“ ‘I asked the mother for permission – energetically,’ he says. ‘At first, she didn’t want our help. But when I showed her we meant no harm, she let us in.

“ ‘She positioned herself below us. Then I asked the calf. When the calf became very still, I reached into her mouth and removed the net.’ The mother and calf swam for 50 meters before pausing to rest.

“Lloreda is one of nine Guardianes del Mar (Guardians of the Sea), a grassroots African-Colombian collective from six coastal communities around Colombia’s Gulf of Tribugá, a biodiversity hotspot on the Pacific coast that spans 600,000 hectares of ocean, forest and mangroves. The region, where dense Chocó rainforest meets the ocean, is a Unesco biosphere reserve and is designated a ‘hope spot‘ by the nonprofit organization Mission Blue for its ecological significance.

“Scuba diving is crucial for identifying and removing ghost fishing gear – lost or abandoned commercial nets made mostly of near-indestructible plastics – but it is prohibitively expensive. With sponsorship from Ecomares and Conservation International, Lloreda and his colleagues have trained not only in diving, but in removing fishing gear from coral with quick, precise and safe techniques.

“Many guardians double as coral gardeners and reef surveyors, collecting data for both their communities and scientific partners. Three, including Lloreda, are trained to free marine animals.

“According to WWF, 50,000 tons of fishing gear are lost or abandoned in the oceans globally each year. These ‘ghost nets’ drift across borders, ensnaring coral, turtles, sharks – and whales. In the Gulf of Tribugá alone, Guardianes del Mar estimates that 3-4 humpback whales become entangled each year. …

“Guardianes del Mar is working to certify more local divers so they can have a greater impact. But it faces mounting logistical and financial hurdles.

” ‘We used to send the nets to Buenaventura for recycling, but fuel costs are too high,’ says Benjamin Gonzales, 53, one of the senior guardians. There are no roads – the communities are connected mainly by boat – so any rubbish or recycling must be transported out by boat or plane.

“Today, the nets are repurposed into bracelets and sold in Germany and locally in Nuquí, the main coastal municipality. Lead weights are melted down into new dive weights for the local shop, run by Guardianes del Mar advocate Liliana Arango.

“The spirit of mutual care between people and nature runs deep in Tribugá, where the population numbers about 7,000. African-Colombian communities here are descended from formerly enslaved people who escaped Spanish rule and crossed the jungle to reach the coast. They were welcomed by the Indigenous Emberá, and today co-govern the region through a state-recognized model of local autonomy. …

“Says Camilo Morante, 25, the youngest guardian and the group’s legal representative … ‘Everyone in this community fishes, so we can’t tell anyone to stop using nets. … The most important thing is that we raise consciousness locally so that we understand the consequences of our actions.’ “

More at the Guardian, here.