Photo: Alex Majoli/Magnum.

“Since at least the time of Greek philosophers, many writers have discovered a deep, intuitive connection between walking, thinking, and writing,” says Ferris Jabr at the New Yorker.

Charles Dickens kept few notes about where his plots were headed. From what I’ve read about him, he kept it all in his head, forming and saving his ideas on long walks wherever he was at the time.

In today’s article, we learn a bit about the science of that.

Ferris Jabr writes, “In Vogue’s 1969 Christmas issue, Vladimir Nabokov offered some advice for teaching James Joyce’s Ulysses: ‘Instead of perpetuating the pretentious nonsense of Homeric, chromatic, and visceral chapter headings, instructors should prepare maps of Dublin with Bloom’s and Stephen’s intertwining itineraries clearly traced.’ He drew a charming one himself. Several decades later, a Boston College English professor named Joseph Nugent and his colleagues put together an annotated Google map that shadows Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom step by step. The Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain, as well as students at the Georgia Institute of Technology, have similarly reconstructed the paths of the London amblers in Mrs. Dalloway.

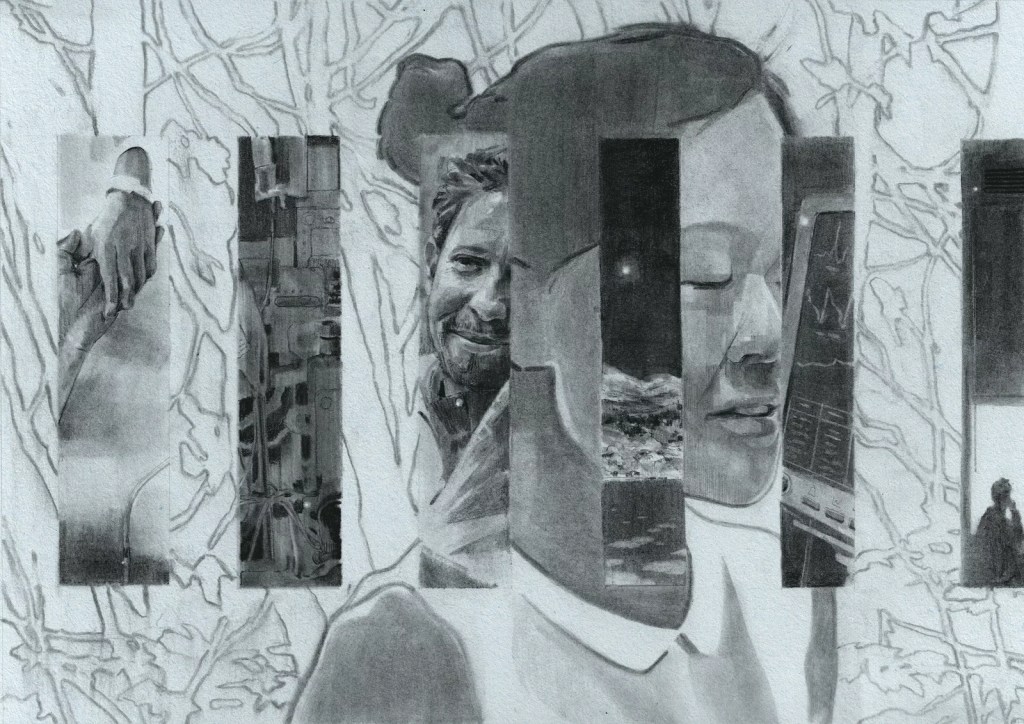

“Such maps clarify how much these novels depend on a curious link between mind and feet. Joyce and Woolf were writers who transformed the quicksilver of consciousness into paper and ink. To accomplish this, they sent characters on walks about town. As Mrs. Dalloway walks, she does not merely perceive the city around her. Rather, she dips in and out of her past, remolding London into a highly textured mental landscape, ‘making it up, building it round one, tumbling it, creating it every moment afresh.’

“Since at least the time of peripatetic Greek philosophers, many other writers have discovered a deep, intuitive connection between walking, thinking, and writing. … ‘How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live!’ Henry David Thoreau penned in his journal. ‘Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.’ Thomas DeQuincey has calculated that William Wordsworth — whose poetry is filled with tramps up mountains, through forests, and along public roads — walked as many as a hundred and eighty thousand miles in his lifetime, which comes to an average of six and a half miles a day starting from age five.

“What is it about walking, in particular, that makes it so amenable to thinking and writing? The answer begins with changes to our chemistry. When we go for a walk, the heart pumps faster, circulating more blood and oxygen not just to the muscles but to all the organs — including the brain. Many experiments have shown that after or during exercise, even very mild exertion, people perform better on tests of memory and attention. Walking on a regular basis also promotes new connections between brain cells, staves off the usual withering of brain tissue that comes with age, increases the volume of the hippocampus (a brain region crucial for memory), and elevates levels of molecules that both stimulate the growth of new neurons and transmit messages between them.

“The way we move our bodies further changes the nature of our thoughts, and vice versa. … When we stroll, the pace of our feet naturally vacillates with our moods and the cadence of our inner speech; at the same time, we can actively change the pace of our thoughts by deliberately walking more briskly or by slowing down.

Because we don’t have to devote much conscious effort to the act of walking, our attention is free to wander. …

“This is precisely the kind of mental state that studies have linked to innovative ideas and strokes of insight. Earlier this year, Marily Oppezzo and Daniel Schwartz of Stanford published what is likely the first set of studies that directly measure the way walking changes creativity in the moment. They got the idea for the studies while on a walk. …

“In a series of four experiments, Oppezzo and Schwartz asked a hundred and seventy-six college students to complete different tests of creative thinking while either sitting, walking on a treadmill, or sauntering through Stanford’s campus. In one test, for example, volunteers had to come up with atypical uses for everyday objects, such as a button or a tire. On average, the students thought of between four and six more novel uses for the objects while they were walking than when they were seated. …

“Where we walk matters as well. In a study led by Marc Berman of the University of South Carolina, students who ambled through an arboretum improved their performance on a memory test more than students who walked along city streets. A small but growing collection of studies suggests that spending time in green spaces — gardens, parks, forests — can rejuvenate the mental resources that man-made environments deplete. Psychologists have learned that attention is a limited resource that continually drains throughout the day. A crowded intersection — rife with pedestrians, cars, and billboards — bats our attention around. In contrast, walking past a pond in a park allows our mind to drift casually from one sensory experience to another, from wrinkling water to rustling reeds.”

More at the New Yorker, here.