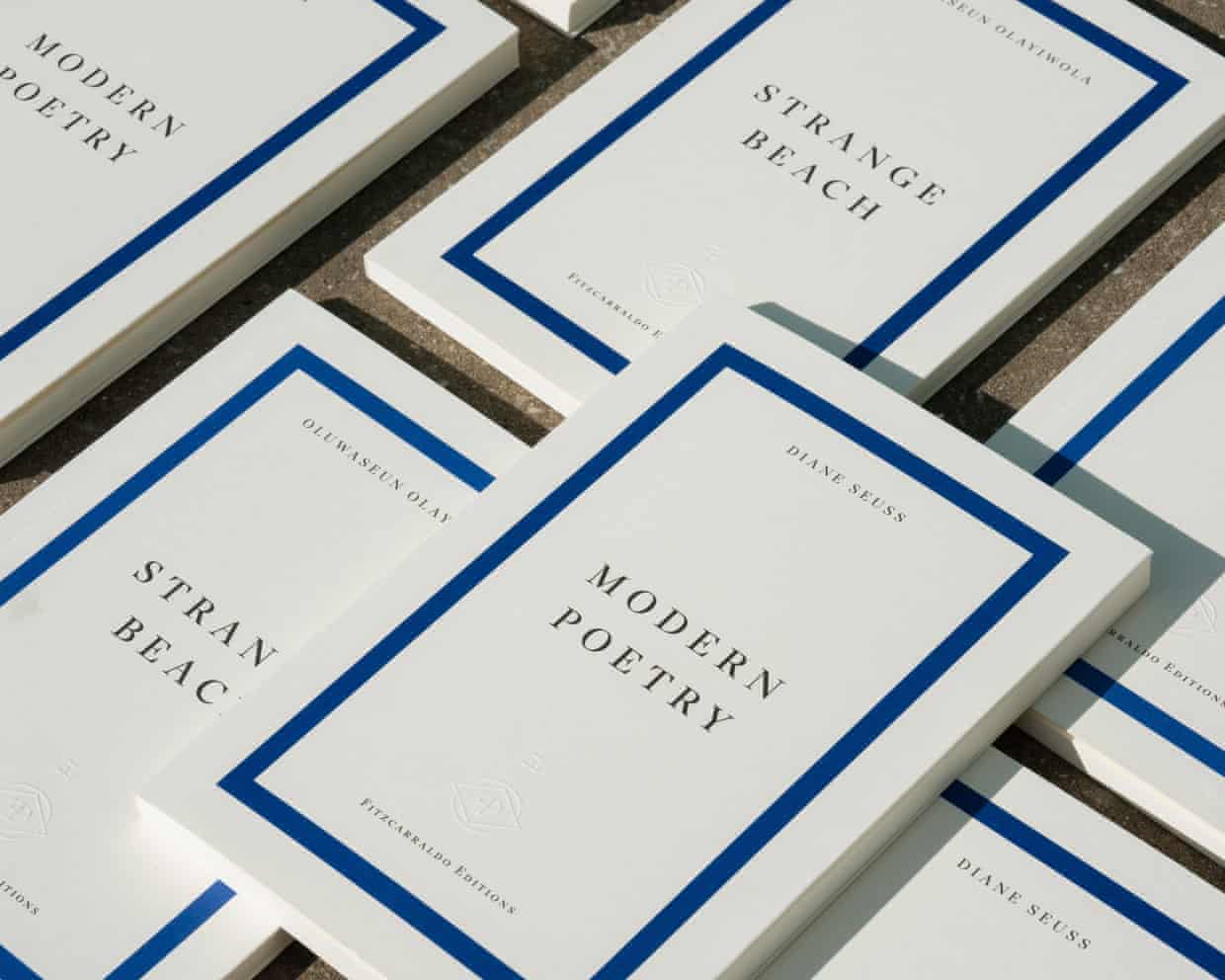

Photo: Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Three publishing companies have launched the biennial Poetry in Translation prize, which will award an advance of $5,000 to be shared equally between poet and translator.

Anyone who has used Google Translate for a simple sentence knows that AI is not going to be doing quality translations of whole books anytime soon. There is too much subtlety needed.

And if that’s true for, say, a murder mystery, imagine how important a human translator is for poetry!

That’s why a new prize for poetry translation from publishers in the UK, Australia, and the US is arriving just in time — before the world gets lulled into thinking an AI translation is just fine.

Ella Creamer reports at the Guardian, “A new poetry prize for collections translated into English is opening for entries. …

“Publishers Fitzcarraldo Editions, Giramondo Publishing and New Directions have launched the biennial Poetry in Translation prize, which will award an advance of $5,000 (£3,700) to be shared equally between poet and translator.

“The winning collection will be published in the UK and Ireland by Fitzcarraldo Editions, in Australia and New Zealand by Giramondo and in North America by New Directions.

“ ‘We wanted to open our doors to new poetry in translation to give space and gain exposure to poetries we may not be aware of,’ said Fitzcarraldo poetry editor Rachael Allen. …

“The prize announcement comes amid a sales boom in translated fiction in the UK. Joely Day, Allen’s co-editor at Fitzcarraldo, believes that ‘the space the work of translators has opened up in the reading lives of English speakers through the success of fiction in translation will also extend to poetry.’ …

“Fitzcarraldo has published translated works by Nobel prize winners Olga Tokarczuk, Jon Fosse and Annie Ernaux. ‘Our prose lists have always maintained a roughly equitable balance between English-language and translation, and some of our greatest successes have been books in translation,’ said Day. ‘We’d like to bring the same diversity of voices to our poetry publishing.’ …

“The prize is open to living poets from around the world, writing in any language other than English.

“The prize is being launched to find works ‘which are formally innovative, which feel new, which have a strong and distinctive voice, which surprise and energize and move us,’ said Day. ‘My personal hope is that the prize reaches fledgling or aspiring translators and provides an opening for them.’ …

“Submissions will be open from 15 July to 15 August. A shortlist will be announced later this year, with the winner announced in January 2026 and publication of the winning collection scheduled for 2027.

“The ‘unique’ award ‘brings poetry from around the world into English, and foregrounds the essential role of translation in our literature,’ said Nick Tapper, associate publisher at Giramondo. ‘Its global outlook will bring new readers to poets whose work deserves wide and sustained attention.’ ”

More at the Guardian, here. I hope a certain blogger who translates Vietnamese poetry into English will apply for that prize.