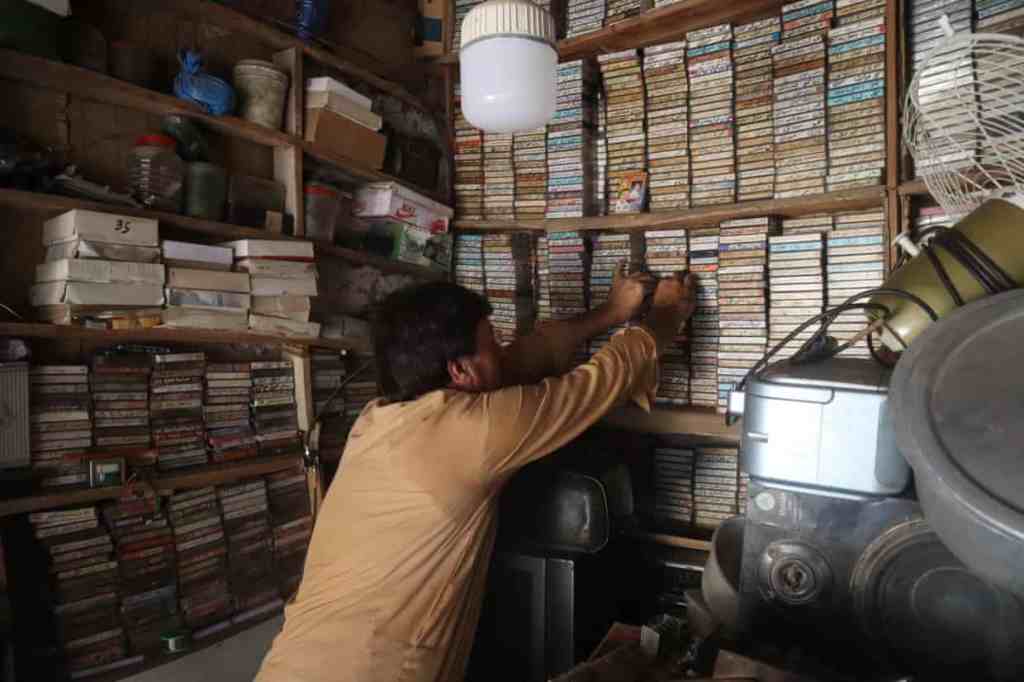

Photo: Sam Odgden via Chamber Music America.

Composer Tod Machover.

With all the furor about artificial intelligence, Rebecca Schmid decided to check in with MIT’s Tod Machover, “a pioneer of the connections between classical music and computers.” Their conversation about how AI applies to music appears on the Chamber Music America website.

“Sitting at his home in Waltham, Massachusetts, the composer Tod Machover speaks with the energy of someone half his 69 years as he reflects on the evolution of digital technology toward the current boom in artificial intelligence.

“ ‘I think the other time when things moved really quickly was 1984,’ he says — the year when the personal computer came out. Yet he sees this moment as distinct. ‘What’s going on in A.I. is like a major, major difference, conceptually, in how we think about music and who can make it.’

“Perhaps no other figure is better poised than Machover to analyze A.I.’s practical and ethical challenges. The son of a pianist and computer graphics pioneer, he has been probing the interface of classical music and computer programming since the 1970s.

“As the first Director of Musical Research at the then freshly opened Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (I.R.C.A.M.) in Paris, he was charged with exploring the possibilities of what became the first digital synthesizer while working closely alongside Pierre Boulez.

“In 1987, Machover introduced Hyperinstruments for the first time in his chamber opera VALIS, a commission from the Pompidou Center in Paris. This technology incorporates innovative sensors and A.I. software to analyze the expression of performers, allowing changes in articulation and phrasing to turn, in the case of VALIS, keyboard and percussion soloists into multiple layers of carefully controlled sound.

“Machover had helped to launch the M.I.T. Media Lab two years earlier in 1985, and now serves as both Muriel R. Cooper Professor of Music and Media and director of the Lab’s Opera of the Future group. …

“Machover emphasizes the need to blend the capabilities of [AI] technology with the human hand. For his new stage work, Overstory Overture, which premiered last March at Lincoln Center, he used A.I. as a multiplier of handmade recordings to recreate the sounds of forest trees ‘in underground communication with one another.’

“Machover’s ongoing series of ‘City Symphonies,’ for which he involves the citizens of a given location as he creates a sonic portrait of their hometown, also uses A.I. to organize sound samples. Another recent piece, Resolve Remote, for violin and electronics, deployed specially designed algorithms to create variations on acoustic violin. …

“Machover has long pursued his interest in using technology to involve amateurs in musical processes. His 2002 Toy Symphony allows children to shape a composition, among other things, by means of ‘beat bugs’ that generate rhythms. This work, in turn, spawned the Fisher-Price toy Symphony Painter and has been customized to help the disabled imagine their own compositions. …

“Rebecca Schmid: How is the use of A.I. a natural development from what you began back in the 1970s, and what is different?

“Tod Machover: There are lots of things that could only be done with physical instruments 30 years ago that are now done in software: you can create amazing things on a laptop. But what’s going on in A.I. is like a major, major difference, conceptually, in how we think about music and who can make it.

“One of my mentors and heroes is Marvin Minsky, who was one of the founders of A.I., and a kind of music prodigy. And his dream for A.I. was to really figure out how the mind works. He wrote a famous book called The Society of Mind in the mid-eighties based on an incredibly radical, really beautiful theory: that your mind is a group of committees that get together to solve simple problems, with a very precise description of how that works. He wanted a full explanation of how we feel, how we think, how we create — and to build computers modeled on that.

“Little by little, A.I. moved away from that dream, and instead of actually modeling what people do, started looking for techniques that create what people do without following the processes at all. A lot of systems in the 1980 and 1990s were based on pretty simple rules for a particular kind of problem, like medical diagnosis. You could do a pretty good job of finding out some similarities in pathology in order to diagnose something. But that system could never figure out how to walk across the street without getting hit by a car. It had no general knowledge of the world.

“We spent a lot of time in the seventies, eighties, and nineties trying to figure out how we listen — what goes on in the brain when you hear music, how you can have a machine listen to an instrument — to know how to respond. A lot of the systems which are coming out now don’t do that at all. They don’t pretend to be brains. Some of the most kind of powerful systems right now, especially ones generating really crazy and interesting stuff, look at pictures of the sound — a spectrogram, a kind of image processing. I think it’s going to reach a limit because it doesn’t have any real knowledge of what’s there. So, there’s a question of, what does it mean and how is it making these decisions?

“What systems have you used successfully in your work?

“One is R.A.V.E., which comes from I.R.C.A.M. and was originally developed to analyze audio, especially live audio, so that you can reconstruct and manipulate it. The voice is a really good example. Ever since the 1950s, people have been doing live processing of singing. The problem is that it’s really hard to analyze everything that’s in the voice: The pitch and spectrum are changing all the time.

“What you really want to do is be able to understand what’s in the voice, pull it apart and then have all the separate elements so that you can tune and tweak things differently on the other side. And that’s what R.A.V.E. was invented to do. It’s an A.I. analysis of an acoustic signal. It reconstructs it in some form, and then ideally it comes out the other side sounding exactly like it did originally, but now it’s got all these handles so that I can change the pitch without changing the timbre. And it works pretty well for that. You can have it as an accompanist, or your own voice can accompany you. It can change pitch and sing along. And it can sing things that you never sang because it understands your voice. …

“The great thing about A.I. models now is that you can use them not just to make a variation in the sound, but also a variation in what’s being played. So, if you think about early electronic music serving to kind of color a sound — or add a kind of texture around the sound, but being fairly static — with this, if you tweak it properly, it’s a kind of complex variation closely connected to what comes in but not exactly the same. And it changes all the time, because every second the A.I. is trying to figure out, How am I going to match this? How far am I going to go? Where in the space am I? You can think of it as a really rich way of transforming something or creating a kind of dialogue with the performer.” Lots more at Chamber Music America, here. No firewall.

I myself have posted about the composer a few times: for example, here (“Tod Machover,” 2012); here (“Stanford’s Laptop Orchestra,” 2018); and here (“Symphony of the Street,” 2017).

“AI Finished My Story. Does It Matter?” at Wired, here, offers additional insight.