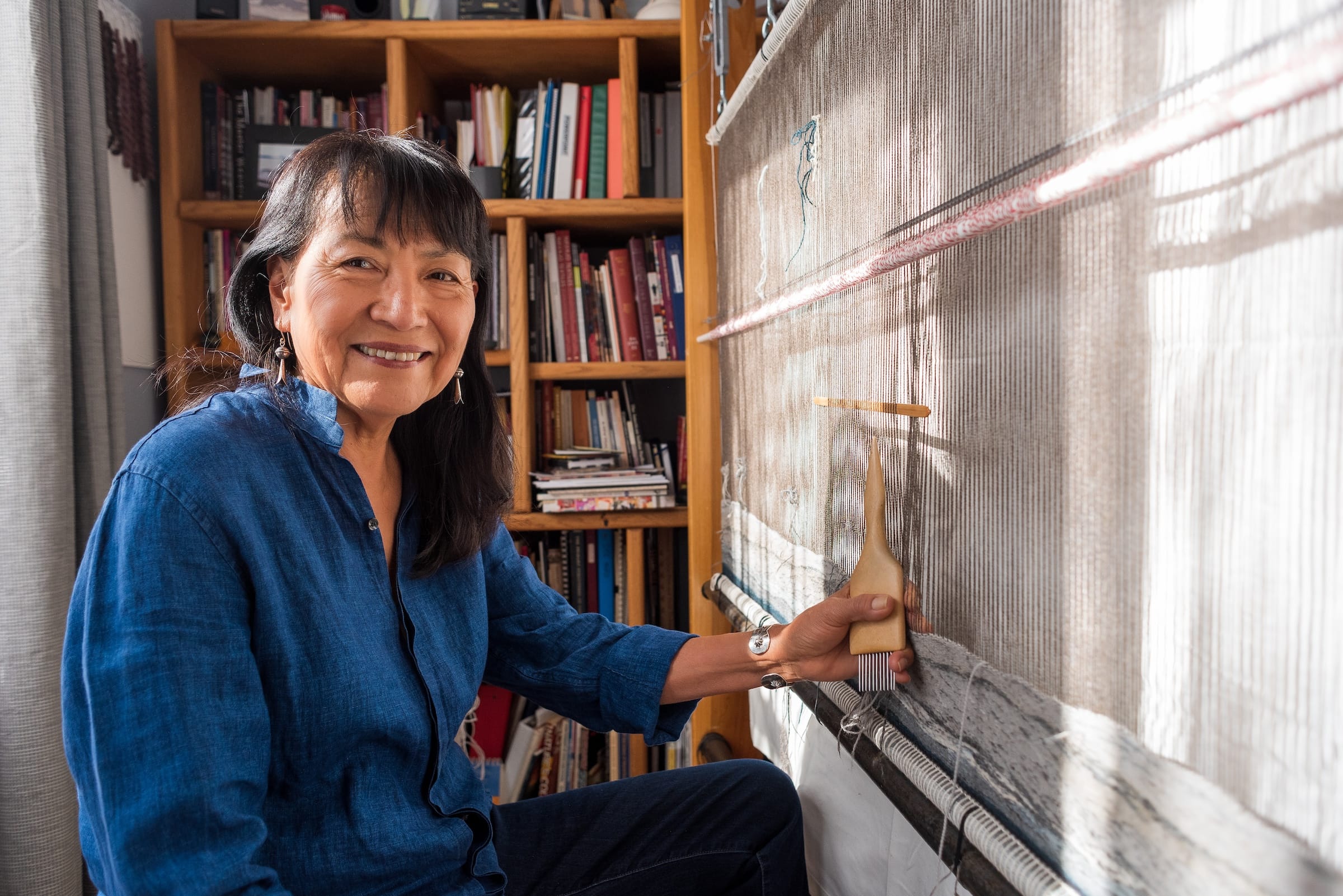

Photo: Peter Ellzey.

DY Begay in her weaving studio in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2022.

Traditions often gain strength and durability when the spirit behind them is reinterpreted through a new generation’s sensibilities. A case in point: the way the weaving and dyeing of Diné artist DY Begay has enriched a traditional Navajo craft.

Sháńdíín Brown and Zach Feuer at Hyperallergic recently interviewed the artist.

They write, “For over four decades, artist DY Begay expanded the expressive range of Diné (Navajo) weaving, transforming the form into a language that is entirely her own. She is a Diné Asdzą́ą́ (Navajo woman), born to the Tótsohnii (Big Water) clan and born for the Táchii’nii (Red Running into Water/Earth) clan. Her maternal grandfather is of the Tsénjíkiní (Cliff Dweller) clan and her paternal grandfather is of the Áshįįhí (Salt People) clan.

“Begay is a fifth-generation weaver who was raised in Tsélání (Cottonwood) on the Navajo Nation, where her family’s sheep flock still resides. Rooted in Diné Bikéyah (Navajo homelands) — from the cliffs of Tsélání to the horizon of the Lukachukai Mountains — her work reflects the blended hues of sunsets, mesas, and mountain ranges, while her use of wool from her family’s flock and natural dyes binds her practice to the land she seeks to honor and protect.

“After graduating from Arizona State University in 1979, Begay moved to New Jersey and immersed herself in the fiber art world of New York City. She studied historic Diné textiles at the Museum of the American Indian, whose collections later became part of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Most of these pieces were created by Diné weavers whose names were not recorded, likely women. She also took inspiration from the work of artists such as Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, and Lenore Tawney — all of whom trained in modern Western traditions yet studied Indigenous weaving practices. …

“When she returned to Tsélání in 1989, her grandmother, Desbáh Yazzie Nez (1908–2003), saw her weavings and urged her to develop her own compositional sensibility. Begay quickly gained recognition at the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market as well as the Santa Fe Indian Market, yet she felt restless in her practice. By 1994, that questioning crystallized into a breakthrough: She began developing color hatching, a method of creating subtle gradations and nuanced color interactions that transformed the solid, banded designs of conventional Diné weaving. …

“In August, Begay spoke with us over Zoom from her home in Santa Fe. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sháńdíín Brown and Zach Feuer

“In Sublime Light: Tapestry Art of DY Begay, the first book dedicated to you and your recent retrospective at the NMAI, you write about watching your mother and grandmother weave in the hogan. …

DY Begay

“I don’t remember the very first time I picked up weaving tools and set a loom on my own. I was very young. I do remember standing behind my mother’s loom, watching her pull colored yarns over and around the warps. Her fingers moved swiftly in and out, pressing the wefts into place. Within minutes, geometric shapes stacked and formed into the outline of a Ganado-style weaving. At that age — maybe four or five — I could not quite comprehend how those shapes came together. I was always perplexed and in awe. Everything happened so fast in front of me as her hands composed lines and rows of colored yarn.

“I grew up surrounded by weavers: my maternal grandmother, my mother, and my aunts. Someone was always at the loom, often positioned in a very central place inside the hogan. And we lived in the hogan when I was growing up, and everybody else did too.

“I watched my mother create stepped patterns with hand-dyed yarns, moving with precision and grace. Teaching came through showing. It was a physical action. The word that I always remember, and is still used today, is kót’é — ‘like this.’ My mother said ‘kót’é, kót’é.’ …

SB & ZF

“Do you remember the moment when you first began weaving yourself — whether your family set up a loom for you or you started working on theirs?

DB

“I was very curious. I tried to hold my mother’s tools, but they were too big for my hands. … Eventually, she allowed me to sit with her once in a while and said ‘kót’é, kót’é.’ I began to get used to the natural action of tapping with the combs. I was about eight years old when I had my own loom. I don’t remember its size. My mother prepared the warp and I used leftover yarn from her bin. I do remember finishing my first weaving, maybe two colors. It was pretty decent for a first attempt. It was a good learning situation because my mother was there. She would sometimes unweave certain parts and we would go on. …

“Most finished weavings, maybe two by three or three by three feet, and some saddle blankets, were taken by my father and my grandfather to the local trading posts to exchange for food, fabric, or whatever was needed. My mother never went to the trading post herself — we didn’t have a vehicle then, so transportation was by wagon or horses. They would roll up the weavings, pack them, and take them to the trading post. …

“In weaving ‘Pollen Path,’ I wanted to share a cultural belief. Among the Diné, we sprinkle corn pollen to honor a new day, to seek blessings, and to bring balance into our lives. Corn itself is a sacred plant. The pollen is collected in late summer, when the tassels of the corn begin to pollinate. We gather it in the early morning, just before the sun rises. For me, ‘Pollen Path’ reflects peace, beauty, and gratitude for life.

“The project began in the summer of 2007, a very good year for growing plants that I use in dyeing my wool. My sister, Berdina Y. Charley, planted local corn seeds she received from our Táchii’nii (Red Running into Water/Earth) relatives. I believe these were heirloom seeds from our Táchii’nii family. …

SB & ZF

“How do you translate the experience of walking in beauty, through the landscapes of Diné Bikéyah (Navajo Country) and more specifically your home of Tsélani (Cottonwood), into the two-dimensional form of weaving?

DB

“Not only do I have my Tsélani landscape embedded in my mind, but I frequently photograph the surrounding textures at various times of the day to capture different lighting as it reflects on the terrain. …

SB & ZF

“Can you tell us about your color palette and the process of dyeing the wool? Is it essential for you to use and make dyes that are from the earth?

DB

“I have been practicing and experimenting with natural dyes for quite a while, and I love using local plants to create my color palette. It is both essential and traditional in my culture to use what the earth provides to create dyes for our yarn.

“My palette comes from many sources. I work with common plants such as cota (Navajo tea), chamisa, rabbitbrush, and sage. I also use non-native materials like insects, fungi, foods, and flowers. Each has its own season, and I collect plants according to the time of year.

“The process itself is an experiment every time. I’ve studied many dyeing methods and learned to be attentive to formulas that help obtain and preserve the colors. For me, making dyes from the earth is not only practical but also deeply connected to tradition and creativity.”

More at Hyperallergic, here. No paywall. Subscriptions encouraged.