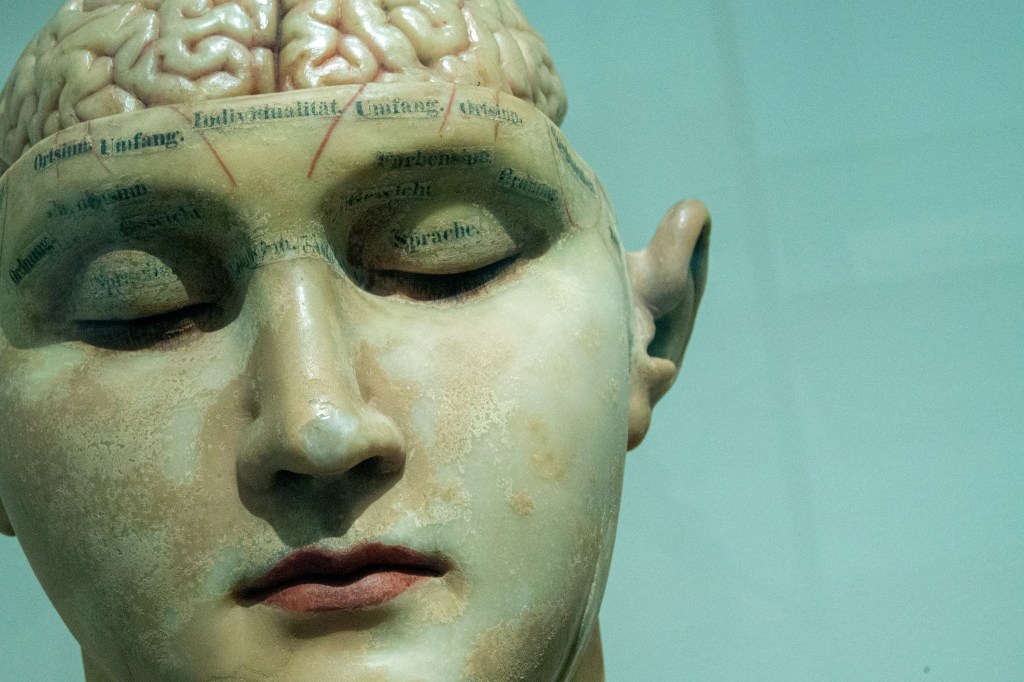

Photo: Nilo Merino Recalde.

A visual representation of an audio clip of five different great tit birds singing one song each.

There is so much for humans to learn about other species! The other day, a post on household pets reacting to the animated film Flow inspired Deb in Tennessee to conduct her own experiment with her dog. She learned that Buster, for one, was bored by Flow, failing to replicate the anecdotal evidence of curiosity described at the New York Times — a good example of why studies usually say, “More research is needed.”

Today we learn something new about birds, but maybe it’s only certain birds.

Victoria Craw writes at the Washington Post, “They sound beautiful, herald the start of spring, and even have the power to reduce stress and boost mental health.

“Now it turns out that some birdsongs also contain a hidden world of shared language, with varying local accents and dialects that change depending on the age of the bird and its peers — not unlike human songs.

“ ‘Just as human communities develop distinct dialects and musical traditions, some birds also have local song cultures that evolve over time,’ said Nilo Merino Recalde of the University of Oxford’s biology department, who led the new research published in the journal Current Biology. ‘Our study shows exactly how population dynamics — the comings and goings of individual birds — affect this cultural learning process.’ …

“The study is based on analysis of over 100,000 bird songs from at least 242 birds recorded in 2020, 2021 and 2022 in Wytham Woods in Britain’s Oxfordshire — a sprawling 1,000-acre wood where ecological and environmental research is carried out. For the last 77 years it has been the site of the Wytham Great Tit Study showing how two species of tit — the great tit and blue tit — have changed over time. …

“While some birds learn songs from their fathers and others learn continuously from neighbors, great tits are believed to do most of their learning in the first 10-11 months of life. …

“Merino Recalde said he was inspired by his love of birds and interest in social learning in animals, which creates an evolving shared culture reminiscent of the way humans learn languages and music. Theoretical work indicates that factors such as population turnover, immigration and age can affect the evolution of these cultural traits — so far, however, empirical evidence on the subject has been limited.

“His research team focused on the great tit, a small bird that lives just 1.9 years on average. The team recorded the ‘dawn chorus’ from March to May — coinciding with breeding season — using microphones placed near nesting boxes to gather more than 200,000 hours of the ‘simple yet highly diverse songs’ sung by males. Through a combination of physical capture, microchips and an artificial intelligence model, researchers were able to recognize the songs of individual birds and track how they changed over time, showing each bird had a repertoire ranging from one to more than 10 tunes.

“ ‘One of the main findings was that the distance that these birds travel while they are learning the songs, and also the ages of the other birds they interact with … affect how varied their songs become, collectively,’ Merino Recalde said. …

” ‘Homegrown’ songs in areas where birds stay close to their birthplace tend to stay unique, similar to the way in which isolated human communities can develop distinct local dialects over time, the team found.

“Age also had a significant impact, with birds of a similar age singing similar tunes, whereas mixed-age neighborhoods had ‘higher cultural diversity.’

This shows that the older birds can act as guardians of culture as they ‘continue to sing song types that are becoming less frequent in the population,’ researchers said.

“ ‘In this way, older birds can function as “cultural repositories” of older song types that younger birds may not know, just as grandparents might remember songs that today’s teenagers have never heard.’ …

“Merino Recalde said capturing how population changes are reflected in song could provide a future avenue for less invasive research, eliminating the need for capturing and tagging animals, for instance. …

“Professor Richard Gregory, the head of monitoring conservation science at Britain’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), who was not involved with the study, praised the ‘herculean’ effort to analyze such a large data sample over a three-year period and said similar research could be used to highlight ‘critical tipping points’ for a population in future.

“While the great tit is not endangered, Gregory said the study could help inform plans to reintroduce or relocate certain animals, as such conservation efforts may be ‘doomed’ if they don’t take their cultural traits into account. ‘This study reminds us that the details of an animal’s life really matter.’

“Gregory, who is also an honorary professor of genetics, evolution and environment at University College London, said the study also showed that ‘methods of wildlife recording and song analysis are developing at break-neck speed,’ and AI is going to ‘revolutionize conservation science’ by allowing patterns in nature to be identified more readily.”

More at the Post, here. You can listen to an audio clip there.