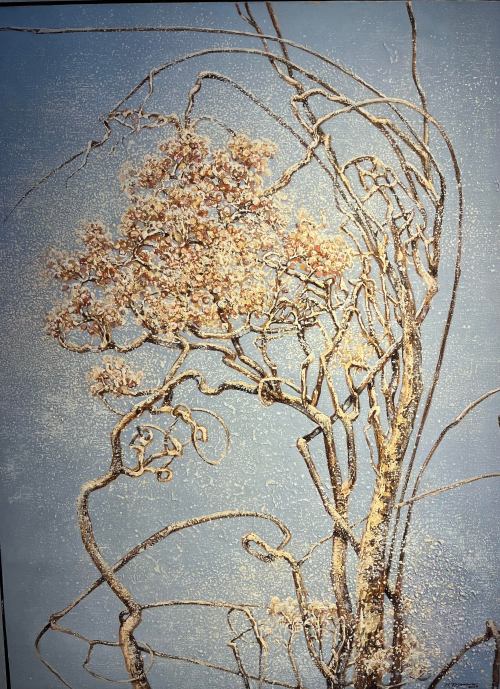

Photo: Nicholas J.R. White.

A night sky above a copse of trees on Guirdil Bay on the Isle of Rum in Scotland.

In the summer, when we are staying in New Shoreham, we can see the stars at night, including the Perseid meteor showers. But the rest of the year, newspaper alerts about cool things happening in the night sky are wasted on us. I would love to see, at least for a little while, what the residents of the Isle of Rum can see.

Kat Hill writes at the New York Times, “Rum, a diamond-shaped island off the western coast of Scotland, is home to 40 people. Most of the island — 40 square miles of mountains, peatland and heath — is a national nature reserve, with residents mainly nestled around Kinloch Bay to the east. What the Isle of Rum lacks is artificial illumination. There are no streetlights, light-flooded sports fields, neon signs, industrial sites or anything else casting a glow against the night sky.

“On a cold January day, the sun sets early and rises late, yielding to a blackness that envelopes the island, a blackness so deep that the light of stars manifests suddenly at dusk and the glow of the moon is bright enough to navigate by.

‘For this reason, Rum was recently named Europe’s newest dark-sky sanctuary, a status that DarkSky International, a nonprofit organization focused on reducing light pollution, has granted to only 22 other places in the world. With the ever-increasing use of artificial lighting at night, places where people can gaze at the deep, ancient light of the universe are increasingly rare.

“Rum’s designation is the result of a long, meticulous bid by the Isle of Rum Community Trust. The effort was led by Alex Mumford, the island’s former tourism manager, and Lesley Watt, Rum’s reserve officer, with the support of Steven Gray and James Green, two astronomers who started Cosmos Planetarium, a mobile theater offering immersive virtual tours of the night sky. Rum ‘stands for something greater,’ Mr. Mumford said, and aspires to be ‘a haven for others to experience the darkness and the Milky Way.’

“A seven-mile walk from Kinloch through the wild and empty heart of the island leads to a Greek-style mausoleum, built in the 19th century, above Harris Bay on the west side of Rum. Locals regard it as the best spot on the island to take in the night sky; on a cloudy night with no moon, one resident said, ‘you can’t even see your hand in front of your face.’ But this night was clear, and stars and meteors wheeled spectacularly overhead as the Milky Way drew a glistening smudge above the brooding mountains, Askival and Hallival. Venus, Saturn and Jupiter stood in a line above the mausoleum’s sandstone pillars.

“Plans are in motion to renovate an abandoned lodge nearby into a place where tourists could stay in their quest for celestial splendor. ‘What you are seeing is not just a 2-D map, but the four dimensions of space and time,’ Dr. Green said. ‘You are looking back into the past.’ …

“On Rum, human life is lived in the small pools of light that spill from windows or glow from headlamps. One key to attaining dark-sky sanctuary status has been to help residents adapt to and embrace the darkness. Porch lights are recessed into doorways and point down; the pier has LED lights, also pointing downward, that provide just enough illumination for marine safety; a shop’s outdoor motion-sensor lights come on only for a few minutes when needed. When the community trust started its sanctuary application in 2022, roughly 15 percent of homes and shops followed the lighting recommendations outlined by the initiative; compliance is now at 95 percent.

“The blackness of night provides more than a cosmic spectacle for humans to enjoy; it is also essential for the environment. ‘Low light levels are important for nocturnal species,’ Ms. Watt said. ‘And artificial lighting can influence the feeding, breeding and migration behavior of many wild animals.’ …

“Education — of adults and children, locals and tourists — is central to dark-sky awareness. Andy McCallum, a teacher on Rum, showed off the models and maps of stars and planets that his handful of students had designed.

“ ‘For our pupils, it’s a powerful reminder that although we live on a small island, we’re part of a vast and interconnected universe,’ he said. It made them proud, he added, to help preserve a unique environment for future generations.”

More at the Times, here. Wonderful photos.