Photo: Gerrit de Bruin/Re-Emerging Films via Wikimedia.

Pianist, jazz singer, and civil rights icon Nina Simone in 1969.

I have been a fan of Nina Simone since my early teens, so I was delighted to read that some of her fans have taken it on themselves to ensure that her childhood home continues to honor her.

Melissa Hellman reports at the Guardian, “It was a surreal experience for Dr Samuel Waymon, Nina Simone’s youngest sibling, to walk back into the renovated childhood home that he once shared with the singer and civil rights activist.

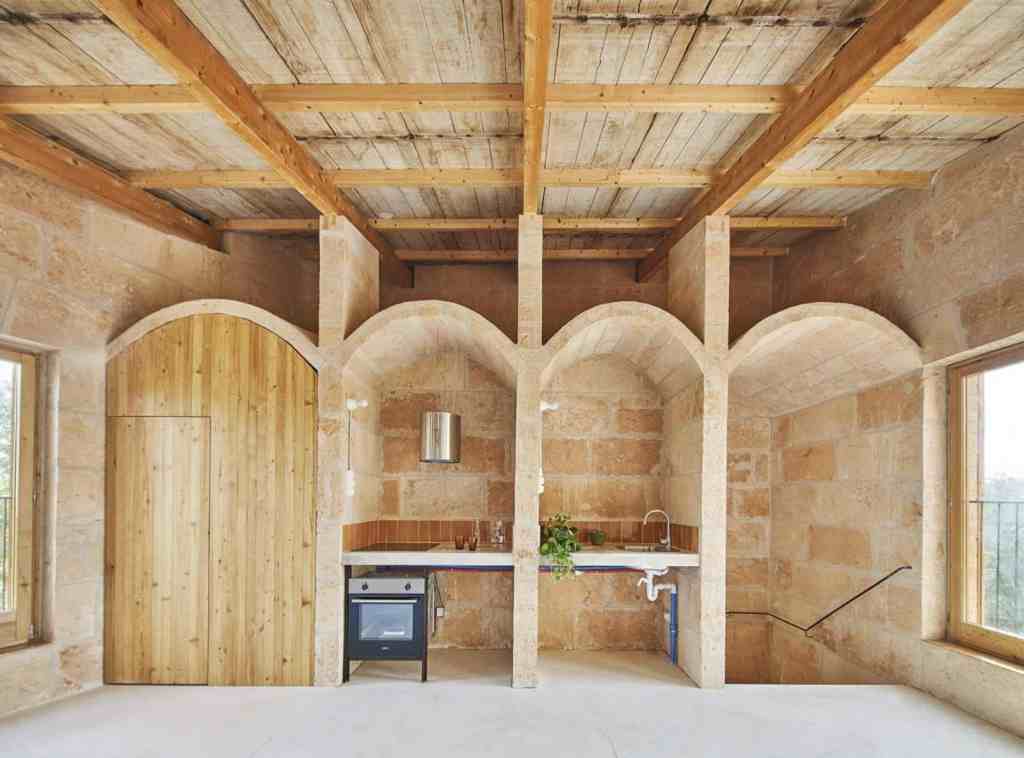

“On that day in the fall of 2025, Waymon, an 81-year-old award-winning composer, said that memories flooded back of him playing organ in the house and cooking on the potbelly stove with his mother as a child in Tryon, North Carolina. He was overjoyed to see the large tree from his youth still standing in the yard. Simone, born Eunice Waymon, lived in the 650 sq ft, three-room home with her family beginning in 1933.

“After sitting vacant and severely decayed for more than two decades, the recently restored home is now painted white, with elements of its former self sprinkled throughout the interior. On the freshly painted mint-blue wall hangs a shadow box that encases the rust brown varnish of the original home. A small piece of the Great Depression-era linoleum sits on the restored wooden floor like an island of the past in a sea of the present.

“ ‘It does conjure up wonderful tears of joy in my heart and in my eyes when I stand in that house, on the porch, going into the rooms where the stove is, and I’m saying, “Wow, this is actually real. The house is restored,” ‘Waymon said. ‘It’s like time travel.’

“The home was bought for $95,000 in 2017 by four Black artists behind the collective Daydream Therapy LLC – the contemporary artist Adam Pendleton, the painter and sculptor Rashid Johnson, the abstract artist Julie Mehretu, and the collagist and film-maker Ellen Gallagher. For them, the structure is an assertion that Black history is worthy of investing in.

“The restoration comes at a time when historians and researchers say that the federal government is attempting to diminish the contributions of Black Americans. A presidential executive order has directed the vice-president, JD Vance, to discontinue spending on programs or exhibits based on race at the Smithsonian Institution and its museums and research centers. The restoration of Simone’s childhood home could serve as an example of how privately funded projects can preserve Black history during a time when federally funded programs are under threat.

“On 1 September, the total rehabilitation of the home was completed after several years of planning and fundraising of nearly $850,000 in materials, construction and engineering costs for the renovation, which began in June 2024. The project has been overseen by the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund (AACHAF), which is now working with a consulting team and the Tryon community to create a long-term management and programming plan for the site. They hope to create a cultural district around the home, which is projected to open to the public for tourism in 2027. …

“Said Tiffany Tolbert, the AACHAF’s senior director for preservation, ‘Being able to preserve the birth or childhood home of these icons, activists and leaders in the African American community is really important so that future generations will understand where we came from. … Having this home still extant, having it where people can visit, where they can learn, is significant because they greatly enhance the understanding of the African American experience in the middle 20th century in itself.’

“When he received a message from a museum curator who alerted him that it was for sale. At first, Pendleton considered other people who might be able to preserve and protect the home, but then he pondered the final line from poet June Jordan’s ‘Poem for South African Women‘: ‘We are the ones we have been waiting for.’ …

“Walking through the home shortly after its purchase, Pendleton was struck by how much he felt the spirit of the home. ‘This is where it all started for Nina, in this humble home,’ he recalled thinking. …

“Now that the home is restored, the AACHAF and a consulting team are working with St Luke’s CME church, where Simone’s mother, Kate Waymon, preached, to incorporate the surrounding East Side neighborhood into future programming. Pendleton sees the future of the home as being a site for reflection, he said, and to ‘become a place where artists go with intention to write music, for example, or to perform in the town. …

“If Simone were to visit the house today, Waymon said that his sister would be amazed and grateful that it has been restored.”

More at the Guardian, here.