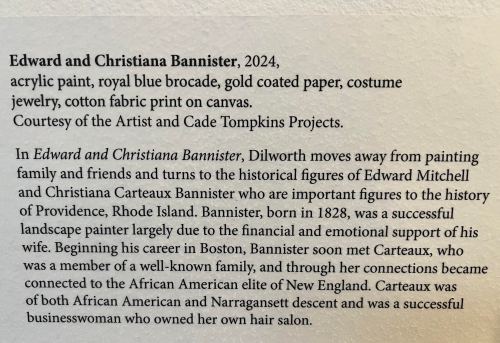

Photo: California Academy of Sciences.

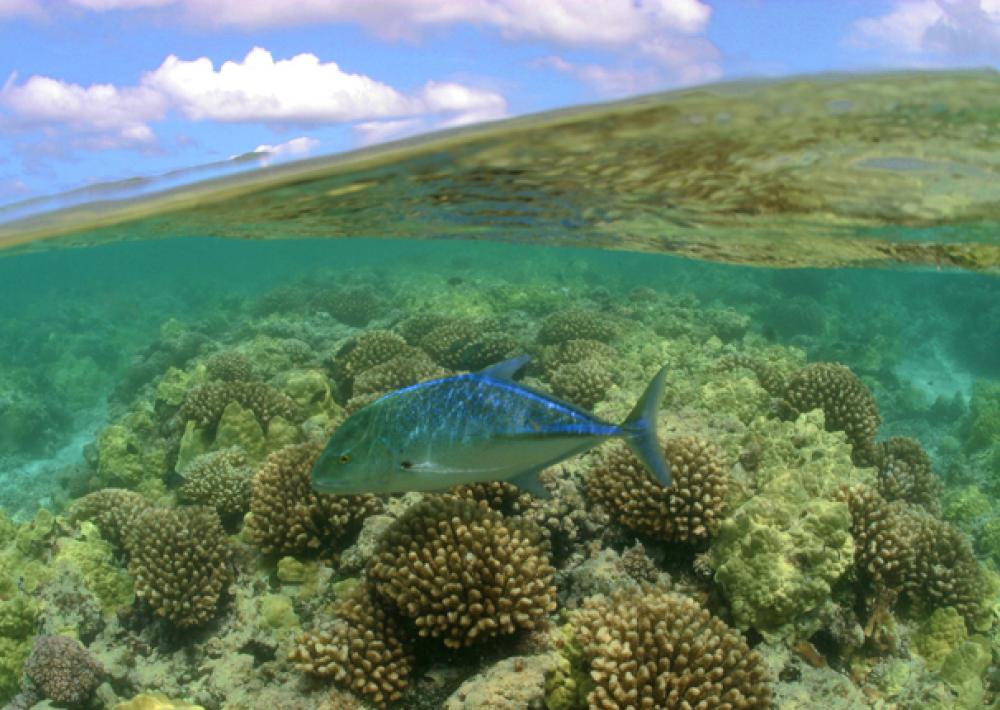

A potentially new species discovered.

Looking ahead at some of the activities scheduled in my retirement community, I see that in February we can attend a lecture by Prof. Peter Girguis, co-director of the Harvard Microbial Sciences Initiative.

The announcement in our app says, “In this presentation, I will take you on a trip through the deep sea, learning about the extraordinary animals and microbes that thrive therein and about their adaptations to this environment. We will also touch on humankind’s relationship with the ocean, the birth of deep-sea biology, and the technological innovations that first took humans into the deep and how we still have time to turn the tide.”

Sounds pretty good, huh? And I think today’s article will have been the perfect preparation for the talk.

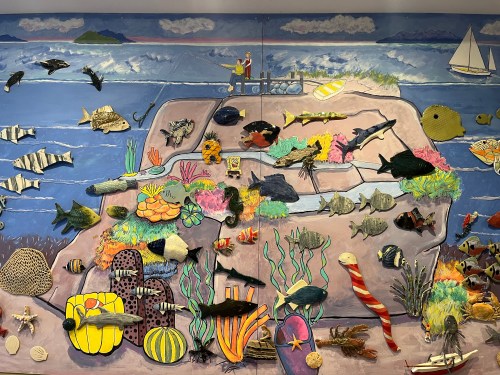

Chandelis Duster reported recently at National Public Radio [NPR] that “scientists believe they have discovered at least 20 new species in a deep part of the Pacific Ocean.

“The discoveries were found after researchers from the California Academy of Sciences retrieved 13 reef monitoring devices that had been placed in deep coral reefs in Guam, which had been collecting data since 2018. The devices, known as autonomous reef monitoring structures or ARMS, were placed up to 330 feet below the surface, an area of the ocean that receives little light.

“Over two weeks in November, scientists retrieved 2,000 specimens, finding 100 species in the region for the first time. Luiz Rocha, California Academy of Sciences Ichthyology curator, told NPR after more analysis is completed, scientists expect to discover more than 20 new species. Rocha was also part of the diving exhibition that placed and retrieved the devices.

” ‘It’s probably going to be higher than that because one of the things we do is we confirm everything with genetics. So we sequence the DNA of the species before we even really make absolutely sure that they’re new,’ Rocha said. ‘And during that process sometimes what happens is what we thought was not a new species ends up being a new species because the genetics is different.’

“He estimates that some of the potential new species could include crabs, sponges, ascidians or sea squirts, as well as new gorgonians, a type of coral.

Deep coral reefs live in an area of an ocean, nicknamed the ‘twilight zone,’ which receives little sunlight.

“Known as the mesopelagic zone, it is a difficult area for some scientists to reach because of pressure and requires specialized diving equipment. Rocha’s team studied the ‘upper twilight zone,’ which sits at 180-330 feet below the surface.

“Finding new species in that part of the ocean was not a surprise for Rocha, who said he and his team were expecting to make new discoveries. But Rocha said he was surprised to see a hermit crab, which usually make their homes in abandoned snail shells, attached to a clam.

“ ‘When they first showed me the picture of it, I’m like, “What, wait, what is that?” I couldn’t even tell what animal it was. And then I realized, oh, it’s a hermit crab, but it’s using a clamshell,’ he said. ‘The species has a lot of adaptations that allows it to do that, and it was really cool and interesting.’

“Rocha and his team have also started a two-year expedition to retrieve 76 more deep reef monitoring devices across the Pacific Ocean, including in Palau and French Polynesia.

“Although studying deep coral reefs may be difficult and challenging, Rocha said it’s crucial to learn more about the reefs and their habitat.”

More at NPR, here.