Photo: Andrew Harnick/AP file photo.

Mellon Foundation president Elizabeth Alexander is one of the people behind a new fund for the literary arts.

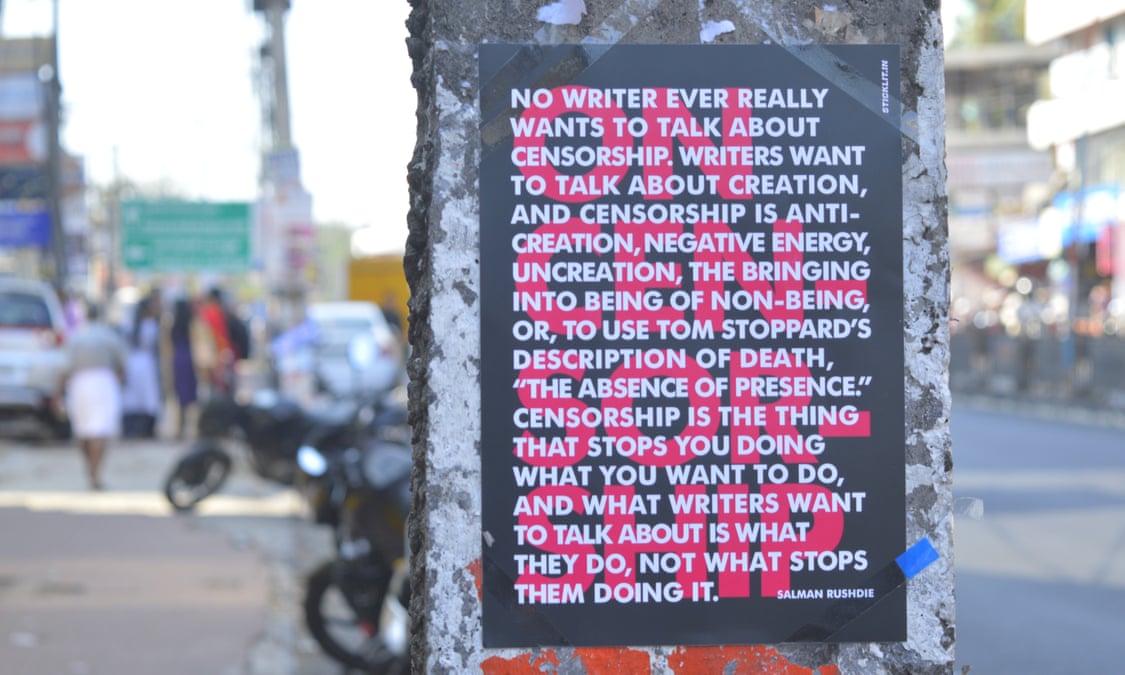

Among the many worthy causes clamoring for our attention at this time of year and in this political climate are those that support the First Amendment, including freedom of the press.

Where I live, we have a nonprofit local newspaper that is sent free to every post box. it was launched with funds from donors and grants and now has the enthusiastic support of all sorts of local advertisers.

For national and international news, I subscribe to the Guardian and the Christian Science Monitor, which are independent of the kind of corporate pressure that contaminates many large television networks and newspapers. Who owns news purveyors really matters. And I believe that ordinary people can help a lot.

Another First Amendment realm that philanthropists have realized need support involves the literary arts — the freedom to write poetry, novels, and other kinds of high-quality books. That’s why a new fund has been started.

HILLEL ITALIE writes at the Associated Press, “Citing a chronic shortage of financial backing for independent publishers and nonprofits dedicated to writing and reading, a coalition of seven charitable foundations has established a Literary Arts Fund that will distribute a minimum of $50 million over the next five years.

“The idea for the fund was initiated by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the country’s largest philanthropic supporter of the arts. Mellon President Elizabeth Alexander cited literature as a vital source of expression.

“ ‘Novelists, poets, and all manner of creative writers have shaped and driven our collective discourse and capacity for invention since the nation’s founding,’ Alexander, an acclaimed poet who joined Mellon in 2018, said in a statement. ‘American philanthropy can and must play a bigger role in strengthening the financial infrastructure of the literary organizations and nonprofits that serve these literary artists.’

“The other participants are the Ford Foundation, Hawthornden Foundation, Lannan Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Poetry Foundation and an anonymous foundation. The project will be overseen by Jennifer Benka, whose previous experience includes serving as executive director of the Academy of American Poets. …

“During a telephone interview with the Associated Press, Alexander emphasized that the literary fund had been in the works well before the National Endowment of the Arts and National Endowment of the Humanities drastically cut back their support this year for virtually every art form. She referred to a 2023 study from the research organization Candid that found literary organizations and individuals were receiving less than 2% of some $5 billion in arts grants awarded in the U.S. … Alexander said support will likely extend across a wide range of recipients, from poetry festivals to writer residencies to small publishers. …

“Percival Everett, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, said in a statement that ‘without nonprofit publishers American letters would have stalled long ago.’ Everett himself was published for decades by an independent press, Graywolf, before moving to Penguin Random House and breaking through commercially with James, which received the Pulitzer in 2024.”

More at AP, here. Please let me know if you have experience with nonprofit publishers.