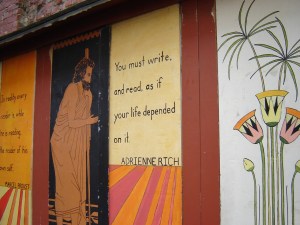

Photo: Riley Robinson/CSM.

Above, Lucy Lujana, a carpenter with United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners Local 54 in Chicago. As of 2023, only 3.1% of carpenters were women. Sometimes they call themselves the “Sisters of the Brotherhood.”

In the US, some women have moved into jobs traditionally held by men, but progress seems slow to me. In countries including India, Australia, Finland, England, and Israel, women have served at the very top, same as being president in the US. America’s oddly progressive and backward character is something to ponder.

Today we consider women in unions.

Richard Mertens writes at the Christian Science Monitor, “Last year, Lisa Lujano, a longtime member of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners Local 54, found herself in very unfamiliar company. She had been tasked to build stairs in one section of the Obama Presidential Center on Chicago’s South Side. When she showed up for work, she discovered she would be part of a crew of five, all women.

“ ‘I don’t know how it came about,’ Ms. Lujano says. … Most of the time, when she shows up for work, she’s the only woman on the crew. And she and her fellow tradeswomen know as well as anyone an inescapable truth: The American construction site is still a man’s world. Until that moment, at least, when suddenly it wasn’t.

“ ‘It was a good experience,’ Ms. Lujano says, looking back on the 11 months working alongside other women carpenters. ‘We were able to relate, be more comfortable with each other. Then she adds, almost exultingly, ‘We’re sisters in the brotherhood!’ …

“Ms. Lujano has been a member of her union for almost 25 years. The journeyman carpenter loves her work, the daily routine. But she still puts up with unpleasant conversations. At lunch she’ll sometimes sit by herself, or take a nap in her car. …

“On a recent Friday, she was … on a team of about 60 workers rebuilding a train station at the edge of the University of Illinois Chicago campus. She’s one of only five women at the site today, the only one on her crew of 10. …

“Over the past decade, the number of women in the construction sector of the U.S. economy has risen steadily, from about 800,000 in 2012 to about 1.3 million in 2023, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Only 11% of jobs in construction industries are held by women, and the majority of these jobs are in office work, sales, or other support services. A growing number are even becoming managers. But on construction sites themselves, the vast majority of construction workers remain men. …

“ ‘The whole process of diversifying the construction trades has been an incredible slog,’ says Jayne Vellinga, executive director of Chicago Women in Trades, an organization that has worked for decades to help women find jobs in the skilled trades.

“[Yet] there’s been a surge in demand for construction workers. … About 94% of construction firms report being unable to hire the skilled workers they need, according to the Associated General Contractors, a trade group in Arlington, Virginia. Experts estimate this shortage numbers more than a half-million workers.

“Given these shortages, the contractors trade group also found last year that 77% of construction companies report that ‘diversifying the current workforce at our firm is critical to strengthening our future business.’

“This doesn’t mean companies will be hiring more women. There remains a significant cultural obstacle to bringing more women into and training them for the skilled trades: Construction is still widely believed to be the domain of men. …

“Like many women, Ms. Lujano followed an unconventional path into the trades. She had no family connections, no uncle or father to bring her into the business, as young men often had. She had dropped out of high school to care for a son who was just a year old. ‘I couldn’t support him,’ she says. …

“In 1998, she saw a flyer from Job Corps, a federal program that offers young people preapprenticeship training and a chance to finish high school. The flyer listed different jobs: plumber, electrician, carpenter, secretary, and more.

“She enrolled in a program in Golconda, a small Illinois town on the banks of the Ohio River. There, over 13 months, she earned a GED certificate and received hands-on training in how to build things. She and other students built ladders, bunk beds, and even frame houses. ‘It was just so cool,’ she says. ‘I ended up loving it.’

“But it wasn’t easy. In her first job she spent four months demolishing and rebuilding porches for a nonunion contractor. Then she got her first union job, working on a bridge in Skokie, just north of Chicago. She was the only woman in a crew of young men in their early 20s. The men would make vulgar comments to her, or about her, even in her presence. …

“Ms. Lujano is no longer a rookie apprentice, but a journeyman carpenter making the full journeyman’s wage: $55 an hour, plus health benefits and a pension. She’s also a union steward, responsible for making sure the workers are properly credentialed and helping them deal with complaints or problems on the job. …

“Looking out over the worksite at the train station in Chicago’s Near North Side, Ms. Lujano sees both good and bad, both progress and the limitations of that progress. Including her with the carpenters, there is one woman among the electricians, one among the ironworkers, one among the bricklayers, and one among the painters. Tradeswomen often feel they are only tokens of diversity on the job site. But to Ms. Lujano, one woman is better than none. …

“Now in her third decade as a union carpenter, she feels keenly the need to help younger women as they face the challenge of working in a world that has, for so long, been dominated by men.”

More at the Monitor, here. No firewall. Subscriptions solicited.