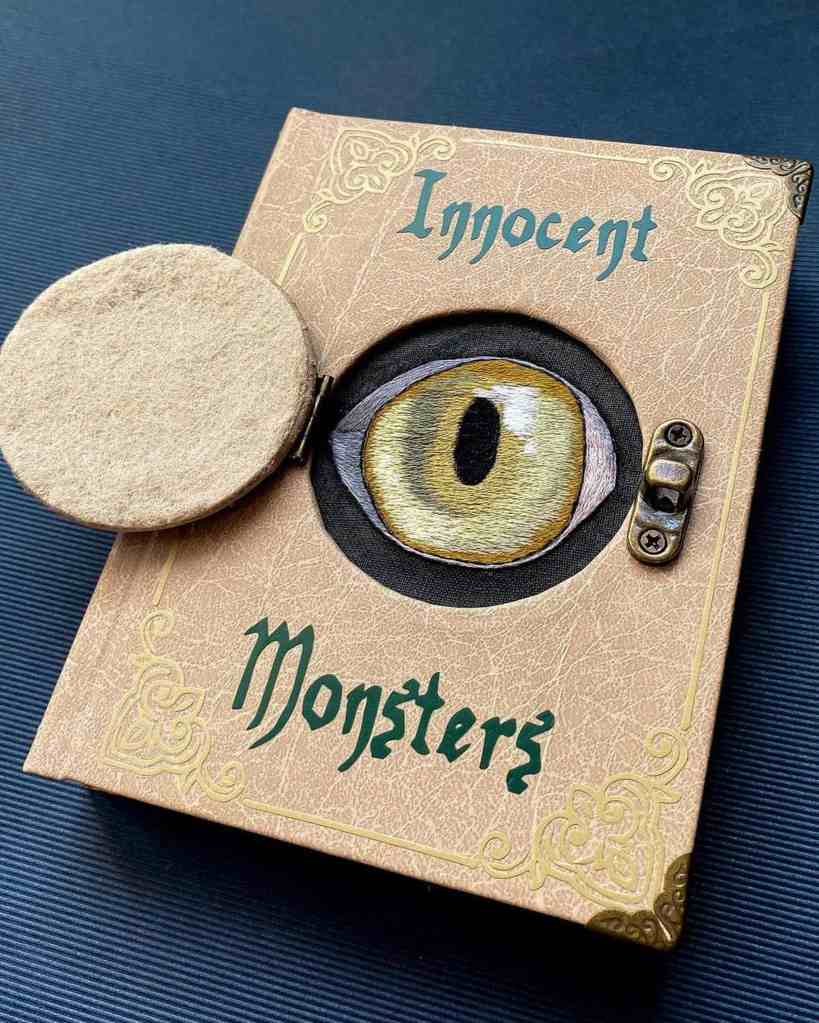

Photo: The Guardian.

Innocent Monsters is an example of a book bound by Geena of ‘beaudelaireslibrary.’ Bookbinding is attracting interest on TikTok.

TikTok comes in for a lot of criticism these days, not least because people think its Chinese ownership enables the Chinese government to spy on the US. For all I know, that could be a legitimate concern, but some activities on TikTok sure seem innocent. I can’t imagine any government secrets hidden in bookbinding lessons, for example.

David Barrett reports at the Guardian about the curious hobby that has taken hold there.

“The videos often begin with every bibliophile’s nightmare: a person ripping the covers off a book. They are not vandals, however; they are bookbinders, taking part in a growing trend for replacing the covers of favorite works to make unique hardback editions, and posting about their creations on TikTok and Instagram.

“Mylyn McColl, a member of the UK-based Society of Bookbinders, runs their international bookbinding competition. She said: ‘It is great to see people taking on our craft and turning their favourite novels into treasured bindings.’ …

“Emma, 28, posts on social media as The Binary Bookbinder, after discovering the hobby a year ago. ‘I was scrolling through social media and I came across a video of someone doing it and was intrigued,’ she said. …

“After a practice attempt with a few sheets of printer paper and some card-stock, Emma, who lives on the East Coast in the US, graduated to re-binding books from her favorite genre, fantasy. ‘It is deeply satisfying re-binding a book to look like it would belong in the world I’m reading about,’ she said. …

” ‘Overall it is a relaxing hobby, but it still comes with its challenges. I like to use my tech background to integrate 3D printed, laser cut, or electronic parts in the books I rebind and that can be difficult.’ …

“A search for ‘bookbinding’ on TikTok produces more than 60 million results, with high-speed time lapse videos showing a brand new product emerging from a mass-produced paperback. Bookbinding tools and equipment include specialist glues, and vinyl cutters for making silhouettes or cameos on covers, which can cost more than £300 [~$384].

“Emma said interest in bookbinding was being driven in part by BookTok, the TikTok genre that has boosted sales for the publishing industry, and the general increase in reading post-pandemic. … ‘Different parts of the same story will resonate with people, so owning a copy of a book that has your favourite quote, image or symbol from the book on the cover is something special.’

“McColl, of the Society of Bookbinders, said: ‘Historically the society was made up predominantly by older people, often retirees enjoy new free time. But that is changing … on the London committee there are now people in 20s, 30s, 40s.’

“Some bookbinders do it for their own enjoyment, while others sell their creations through platforms like Etsy. Geena, who posts on Instagram as baudelaireslibrary, saw it as an opportunity to give physical form to a genre generally only available online – fan fiction.

“The 33-year-old from Wiltshire said: ‘I started bookbinding nearly a year ago. I had been reading Harry Potter fan fiction for about two years. … I had absolutely previous knowledge on how to create a book – I didn’t know it was possible to do at home without commercial equipment.’

“Geena says bookbinding encompasses ‘four or five hobbies,’ allowing her to use skills from her other pastimes, such as embroidery and crochet. She says, ‘With the rise of screens dominating people’s time, I think that creative hobbies where you use your hands and make something from scratch bring a simple joy that [people] haven’t experienced before. It taps into a part of the brain that can improve mental health, and is a real mood booster.’

“Geena says she has made new friends through the hobby, and is hoping to attend a meet-up of British amateur bookbinders later this year. Emma has attended meet-ups in the US. She said: ‘The community aspect is wonderful, and I’ve really been able to bond with people across the world.’

“Jennifer Büchi of the American Academy of Bookbinding, based in Colorado, said there had been a shift in how people discovered the hobby. …

” ‘We saw a big increase in students who’d started learning to bind books online and through social media after the pandemic. It’s been great for us because there’s a lot more interest in our classes – our introductory courses fill up within hours of being posted. Anything that drives interest in the book ultimately helps more students find us, and more students means more folks carrying the craft forward.’ ”

More at the Guardian, here.