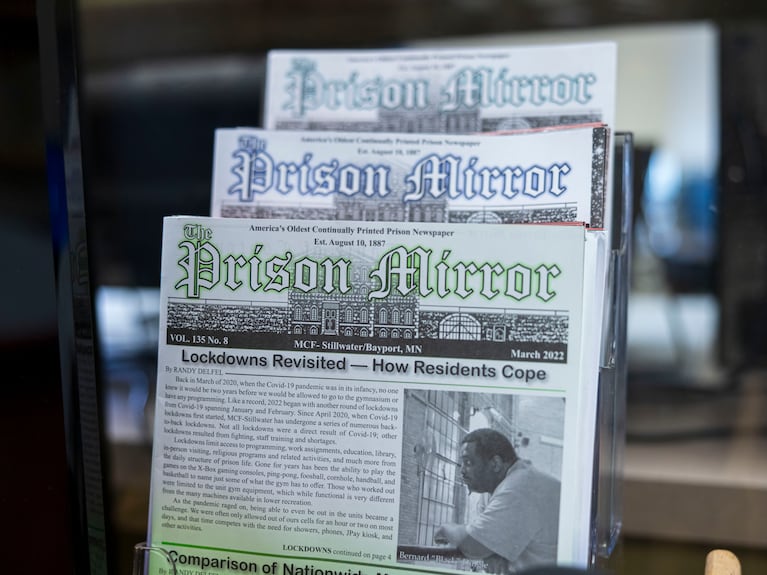

Photo: Kerem Yücel/MPR News via Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Previous issues of the Prison Mirror, which has been publishing since 1887, sit on display in the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Stillwater.

From time to time I like to run a story about interesting prison programs or ex-offenders trying to make good. I’m pretty sure we don’t have the right kind of prisons in the US. You may recall me writing about the system in Norway, which is completely different. (Click here and here.)

Meg Anderson (Minnesota Public Radio NPR) wrote recently about a longtime enrichment program at a prison in Minnesota.

“Inside a state prison near Stillwater, Minn., past the guards and the wings of cells stacked one on top of another, tucked in the corner of a computer lab, Richard Adams and Paul Gordon are fervently discussing grammar.

“Both men are on staff at the Prison Mirror, a newspaper made by and for the people held at the Minnesota Correctional Facility – Stillwater. Gordon had written a profile on the prison art instructor. He read it aloud to Adams. …

“Conversations like this have been happening in this prison for more than a century. The Prison Mirror is one of the oldest prison newspapers in the country, running since 1887. Publications like this aren’t common, but in an era where many journalism outlets in the free world are struggling to thrive amid scores of layoffs, journalism behind bars is actually growing.

“ ‘Overall we do see a growth and a lot of interest in starting publications, starting podcasts even. And so that’s really quite exciting,’ says Yukari Kane, CEO of the Prison Journalism Project.

“Thirty years ago, she says there were estimated to be only six prison newspapers. Today, there are more than two dozen. That doesn’t take into account the hundreds of incarcerated writers submitting work to publications on the outside, like The Marshall Project’s Life Inside series.

“Kane says this kind of work can offer a window into what prison is actually like, one that prison administrators aren’t necessarily going to offer up freely. … Even if a newspaper doesn’t circulate far beyond the prison yard, it can offer a sense of empowerment for its writers. …

“The Stillwater prisoners write book reviews, legal explainers, and summaries of local, national and international events for the monthly newspaper. One man recently submitted an essay on homesickness. Another wrote an editorial criticizing lockdowns. The men on staff — there are only three of them — had to apply for these unpaid jobs, and they’re highly sought after.

“Adams says the job requires a lot of reading and research about what’s going on around the world and the prison. There are challenges. They don’t have the internet, for instance, so they have to rely on print media and articles printed out by prison staff.

“The prison also has to approve everything the paper publishes. The men say that can limit what they write about, especially if they want to report on the harsher aspects of their lives.

“ ‘I am limited in the sense of, they’re not going to let me print all types of crazy things about the water or the lockdowns or getting restrained or anything like that, which is understandable to a degree,’ Gordon says.

“Last fall, around 100 Stillwater prisoners refused to return to their cells. Gordon says the disobedience was their way of protesting extreme heat, poor water quality, and staffing shortages, which he says often result in lockdowns. He plans to write about it, but says he has been retaliated against in the past for sending reporting to outside publications.

“ ‘I was a lot more aggressive in my writing back then, and that was a learning experience for me,’ he says.

Brian Nam-Sonenstein, a senior editor at the Prison Policy Initiative, says punishment for doing journalism behind bars is common. ‘You can lose what are called good time credits, which are essentially time off of your sentence based on good behavior. You could go to solitary confinement. You could have your privileges revoked,’ he says. …

“Marty Hawthorne works at the Stillwater prison and oversees the Prison Mirror.

“ ‘They have a lot of freedom. My philosophy is: It’s their newspaper. It’s not my newspaper,’ he says. ‘I believe they have a right to do what they’re doing.’ He says if the men plan to publish something critical, he makes sure whoever they’re writing about has an opportunity to respond. But he says he also pushes back when leadership tries to censor stories he believes are fair.”

More at NPR, here. No firewall.