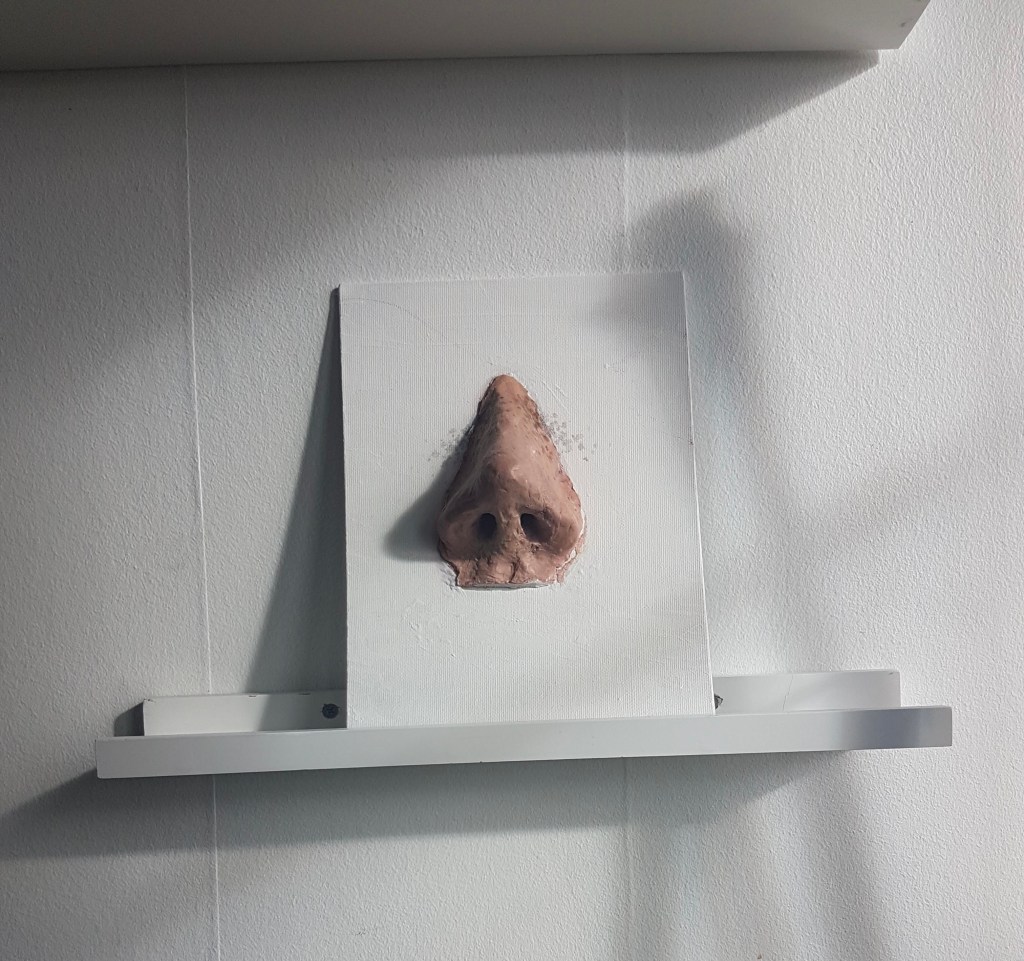

Photo: Lorianne Willett/KUT News.

Dr. Tyler Jorgensen sets “A Charlie Brown Christmas” on a record player at Dell Seton Medical Center in Austin, Texas. He uses vinyl records as a form of music therapy for palliative care patients.

We’ve had a lot of posts about how playing music from a patient’s youth affects those with dementia. It’s like watering a dry plant. The patient perks right up and often starts singing along. Now a doctor in Texas has found that old musical memories have a pleasing affect on people in palliative care, too.

Olivia Aldridge writes at National Public Radio [NPR], “Lying in her bed at Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas at Austin, 64-year-old Pamela Mansfield sways her feet to the rhythm of George Jones’ ‘She Thinks I Still Care.’ Mansfield is still recovering much of her mobility after a recent neck surgery, but she finds a way to move to the music floating from a record player that was wheeled into her room.

” ‘Seems to be the worst part is the stiffness in my ankles and the no feeling in the hands,’ she says. ‘But music makes everything better.’

“The record player is courtesy of the ATX-VINyL program, a project dreamed up by Dr. Tyler Jorgensen to bring music to the bedside of patients dealing with difficult diagnoses and treatments. …

” ‘I think of this record player as a time machine,’ he said. ‘You know, something starts spinning — an old, familiar song on a record player — and now you’re back at home. …

“The man who gave Jorgensen the idea for ATX-VINyL loved classic rock. That was around three years ago, when Jorgensen, a long-time emergency medicine physician, began a fellowship in palliative care — a specialty aimed at improving quality of life for people with serious conditions, including terminal illnesses.

“Shortly after he began the fellowship, he says he struggled to connect with a particular patient. …

“He had the idea to try playing the patient some music.

“He went with ‘The Boys Are Back in Town,’ by the 1970s Irish rock group Thin Lizzy, and saw an immediate change in the patient.

” ‘He was telling me old stories about his life. He was getting more honest and vulnerable about the health challenges he was facing,’ Jorgensen said. …

“Jorgensen realized records could lift the spirits of patients dealing with heavy circumstances in hospital spaces that are often aesthetically bare. And he thought vinyl would offer a more personal touch than streaming a digital track through a smartphone or speaker.

” ‘There’s just something inherently warm about the friction of a record — the pops, the scratches,’ he said. ‘It sort of resonates through the wooden record player, and it just feels different.’

“Since then, he has built up a collection of 60 records and counting at the hospital. The most-requested album, by a landslide, is Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Rumours’ from 1977. Willie is also popular, along with Etta James and John Denver. And around the holidays, the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’ gets a lot of spins.

“These days, it’s often a volunteer who rolls the record player from room to room after consulting nursing staff about patients and family members who are struggling and could use a visit. …

“Often, the palliative care patients visited by ATX-VINyL are near the end of life. Jorgensen feels that the record player provides an interruption of the heaviness those patients and their families are experiencing. Suddenly, it’s possible to create a new, positive shared experience at a profoundly difficult time. …

“Other patients, like Pamela Mansfield, are working painstakingly toward recovery. She has had six neck surgeries since April, when she had a serious fall. But on the day she listened to the George Jones album, she had a small victory to celebrate: She stood up for three minutes, a record since her most recent surgery. With the record spinning, she couldn’t help but think about the victories she’s still pursuing.

” ‘It’s motivating,’ she said. ‘Me and my broom could dance really well to some of this stuff.’ “

More at NPR, here. For a different angle on music at the end of life, check out a Guardian story on a documentary about the Threshold singers, here.

Photo: Richard Saker for the Guardian

Photo: Richard Saker for the Guardian