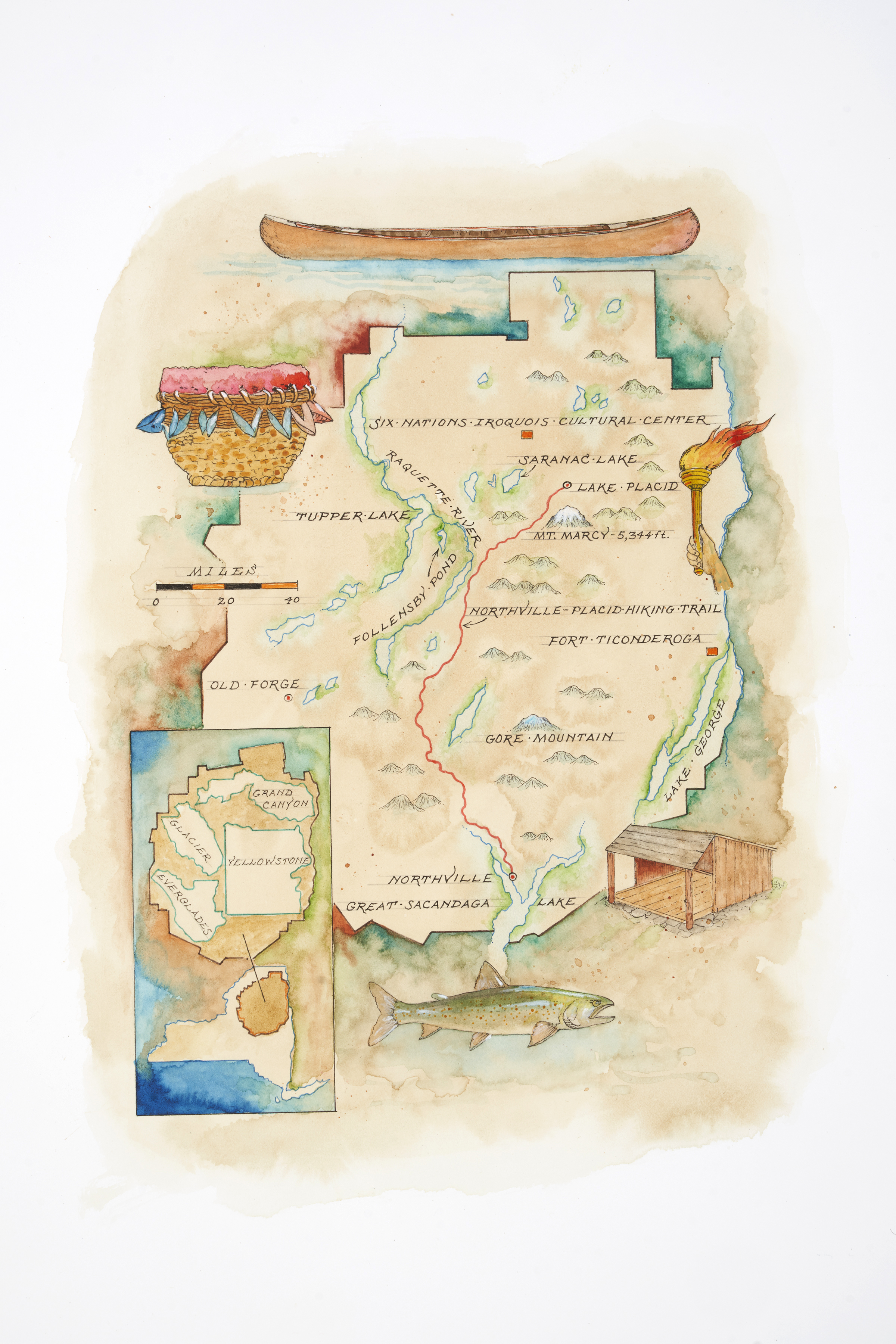

Art: Michael Francis Reagan.

Adirondack Park covers one-fifth of New York State — larger than Yellowstone, Yosemite, and many other national parks combined. It differs from those national parks, says the Nature Conservancy, in that it combines existing towns, businesses, recreation, and wilderness.

When I was very young, I used to visit a great aunt who had a “camp” in New York State’s beautiful Adirondacks. It’s all coming back to me as I read Ginger Strand’s article in the Nature Conservancy magazine.

She begins by describing a meeting she had with scientists at Follensby Pond.

“This place served as timberland for over a hundred years and was privately owned by different families, but it still has a primeval feel … a unique, interlinked landscape of forest, streams, wetlands and rare silver maple floodplains. In 2008, The Nature Conservancy bought this vast parcel of land from the estate of the former owner. In addition to Follensby Pond, the 14,600-acre property includes 10 miles along the Raquette River, a prime paddling waterway that makes up part of the longest inland water trail in the United States. …

“It was widely expected that TNC would sell the land to the state of New York. Instead, to the surprise of everyone, including itself, TNC concluded that the property needed a special level of management and protection, and kept it. In 2024 the Nature Conservancy sold two conservation easements to the state. The easements opened part of the parcel to recreational access and designated the rest of it as a freshwater research preserve with managed public access. …

“The 6-million-acre Adirondack Park, covering one-fifth of New York state, is the largest park in the lower 48 states. But it differs from national parks, like Yellowstone or Yosemite, and state parks, which are typically set aside for recreation or wildlife. Managed by two state agencies, the park has no gates or entry fees, and it’s peppered with small towns, farms, timberlands, businesses, and hunting camps, all nestled among forests, mountains, rivers, and lakes. All told it is one of the largest tracts of protected wilderness east of the Mississippi, and if it had a heart, it would be right about at Follensby Pond.

“Follensby Pond is not really a pond, but rather a 102-foot-deep lake slightly larger than Central Park. For the local Haudenosaunee and Abenaki, it was a hunting area, accessed via canoe routes that traversed the Raquette River, the historic ‘highway of the Adirondacks.’ … Tourists sought it out until the 1890s, when a timber company bought the land. In private hands, it became a family retreat as well as timberland. …

“In 2008, the Nature Conservancy closed on the Follensby property. Just about everyone expected the organization to sell it to New York state to become part of the Adirondack Forest Preserve. But with the economy entering a recession, the state had no funds to buy another big parcel. Under no time pressure to transfer the land, TNC began studying it. …

“To start, TNC hosted a ‘bioblitz,’ bringing 50 scientists — geologists, soil scientists, ecologists, fish experts — onto the land to survey its flora and fauna. What the science showed was that this property wasn’t just historically vaunted; it was ecologically significant. The lake in particular held a ‘functioning ecosystem that is almost as intact as they come,’ says Michelle Brown [Michelle Brown, a senior conservation scientist for TNC in New York]. …

“This lake harbors a population of freshwater lake trout. And not just any lake trout — ‘old-growth’ lake trout, according to past research led by McGill University. Because of the minimal fishing at Follensby, the trout have been able to grow older than similar trout might in other lakes. …

“The trout’s length here can reach 2 to 3 feet; the record one here weighed 31 pounds. That’s a prized quarry for someone who has been obsessed with fishing since he was four. Yet [Dirk Bryant, who directs land conservation for TNC in New York] loves the idea of keeping the pond and these fish protected.

” ‘The hardest thing for me as an angler was to learn to think differently. … But we’re thinking about our fisheries in climate change. The lake trout is our timber wolf, our apex predator.’ Now, he says, many of the lakes that used to have the trout don’t have them anymore.

“In fact, a 2024 study found that soon only 5% of the lakes in the Adirondacks will be capable of supporting native populations of trout. … Follensby Pond is one of a rare few cool enough and healthy enough to support lake trout. …

“ ‘If you have some intact waters that can support native populations, those are the places that will support adaptation to climate change, as well as providing brood stock for restocking other waters,’ Bryant says. ‘You don’t hunt wolves in Yellowstone.’ …

“Still, when the ‘brain trust’ floated the idea of protecting the pond as a freshwater preserve, it was a surprise to many. … Paddling guidebooks in particular had been anticipating that the Follensby parcel would soon be accessible. The Adirondacks team looked for ways to balance protecting the lake with not turning the area into a conservation fortress.

“ ‘There were all these different needs: public access, Indigenous access, hunting clubs with leases, the fishery, the town,’ [Peg Olsen, TNC’s Adirondacks director] says. ‘We wanted to honor and respect all the stakeholders.’

“They landed on a compromise. The conservation easements sold to New York state create two distinct areas on the Follensby property. On nearly 6,000 acres along 10 miles of the Raquette River, one easement creates new public access for hiking, paddling, camping, hunting and fishing. The other easement protects a nearly 9,000-acre section around Follensby Pond as a freshwater research preserve, guided by a public-private consortium, to collaborate on research and preserve the lake’s unique ecosystem. While making Follensby a living laboratory, it also provides for Indigenous access and managed public access aimed at education.

“Like the wider Adirondack Park, with its combination of private lands, active towns and protected wilderness areas, it, too, will be an ongoing experiment in balancing environmental preservation with human communities.”

Read more at the Nature Conservancy magazine, here.

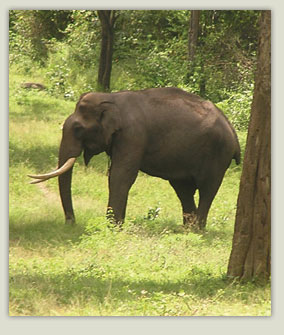

Photos: Sai SanctuaryIn part to preserve the planet’s source of rainwater, this couple bought a sanctuary in India. As it expands, it protects more and more species.

Photos: Sai SanctuaryIn part to preserve the planet’s source of rainwater, this couple bought a sanctuary in India. As it expands, it protects more and more species.