Photo: Kalliopi Stara.

Powdered orchid bulbs are the main ingredient of the popular Middle Eastern drink called salep, or sahlep. But the orchids are endangered.

One of my sources for this blog is the international radio show called The World. It posts recordings of episodes and sometimes transcripts. I like to have a transcript, and if there isn’t one, I try to see if I can find the story elsewhere. Durrie Bouscaren at The World got me interested in today’s topic on some endangered orchids, and then I was able to find a 2023 Atlas Obscura piece to use as text.

Here is Vittoria Traverso writing about the Turkish beverage called salep at Atlas Obscura.

“For Kerem Özcan, a data scientist based in Amsterdam, winters in his home country of Turkey would not have been the same without salep, a hot drink made of crushed orchid roots, milk, and sugar. On ski trips to the mountains of Uludağ, ‘we’d always end the cold and tiring day with a salep,’ he says. Özcan, who left Turkey in 2013, is one of the many Turkish people living abroad who thirsts for salep. ‘I tried to quench it with eggnog a couple times, but it didn’t cut it for me,’ he says.

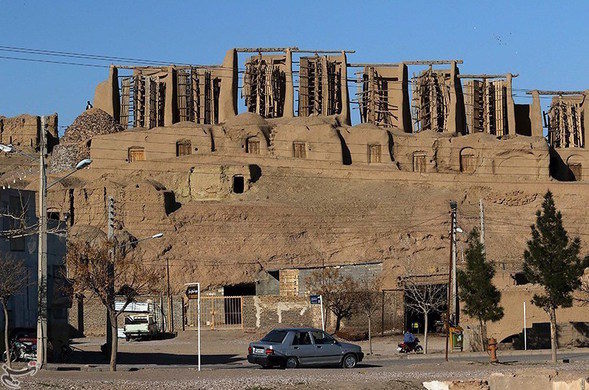

“Much like eggnog, salep is a staple winter drink, and it is enjoyed throughout Turkey, Greece, and parts of the Middle East. Part comfort food and part medicine, it is a popular folk remedy for everything from stomachache to impotence.

“In recent years, increased interest towards plant-based drinks and traditional foods has fueled a surge in demand for salep. But the craze is taking a toll on the drink’s key ingredient.

It can take as many as 13 orchid bulbs to make one cup.

“Currently, wild orchids are considered endangered in many parts of Greece and Turkey due to overharvesting, drought, and habitat degradation.

“It’s hard to say when and where salep originated but historical evidence suggests ancient Greeks and Romans consumed a similar beverage. Özge Samanci, head of the Gastronomy and Culinary Arts Department at Özyeğin University in Istanbul, explains that the Greek doctor Dioscorides described the medical properties of orchid roots in his first-century treatise De materia medica. Roman doctors also used bulbs to prepare a beverage called satyrion, a Latin word for orchid, as an aphrodisiac.

“During the Ottoman Empire, salep was a medicinal staple. ‘There is evidence that salep was consumed in palaces of the Ottoman Empire as early as the 15th century,’ Samanci explains. …

A journal entry by Jane Austen in 1826 describes the taste of salop as ‘nectar.’

“ ‘Tea is great, coffee greater; chocolate, properly made, is for epicures; but these are thin and characterless compared with the salop swallowed in 1826,’ Austen wrote.

“While salep is no longer a part of English daily life, it is still considered a winter must in Turkey. … Until recent times, salep was considered a special treat. ‘Drinking salep is usually a moment of luxury,’ Samenci says. ‘It’s not something you drink four times a day like coffee.’ …

“Interest in traditional and more wholesome foods is putting pressure on salep’s key ingredient. Orchid powder is made from the bulbs from the Orchis, Ophrys, and Dactylorhiza which include about 109 species of orchids mostly native to North Africa and Eurasia. In order to make salep powder, also known as ‘white gold’ for its market value, foragers dig orchid plants out of the soil with small shovels. Then, the round roots of each plant are harvested, cleaned, boiled, dried, and crushed into powder. This orchid powder can sell for up to 80 US dollars per pound.

“A few farms do cultivate orchids for salep, but it’s a difficult and expensive endeavor. The vast majority are still foraged in the wild. Most wild orchids used to make salep are listed as protected species under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) which regulates the trade of endangered animals and plants. In theory, protected orchid plants should be traded across national borders only with documentation certifying that they have been harvested or cultivated sustainably. However, orchids are one of the most sought-after species on online platforms that sell illegally sourced wildlife. …

“Susanne Masters, an ethnobotanist at Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands [advises] people to avoid consuming salep at all to avoid further endangering wild orchids. ‘To consume salep sustainably you would need to be growing your own, or personally know and trust a person who is a custodian of a landscape in which the orchids used for salep are growing.’ ”

The long, fascinating article is at Atlas Obscura, here.

Durrie Bouscaren first got me interested with her update at Public Radio International’s The World. You can listen to her story here. No paywall for either site.