Photo: John Okot.

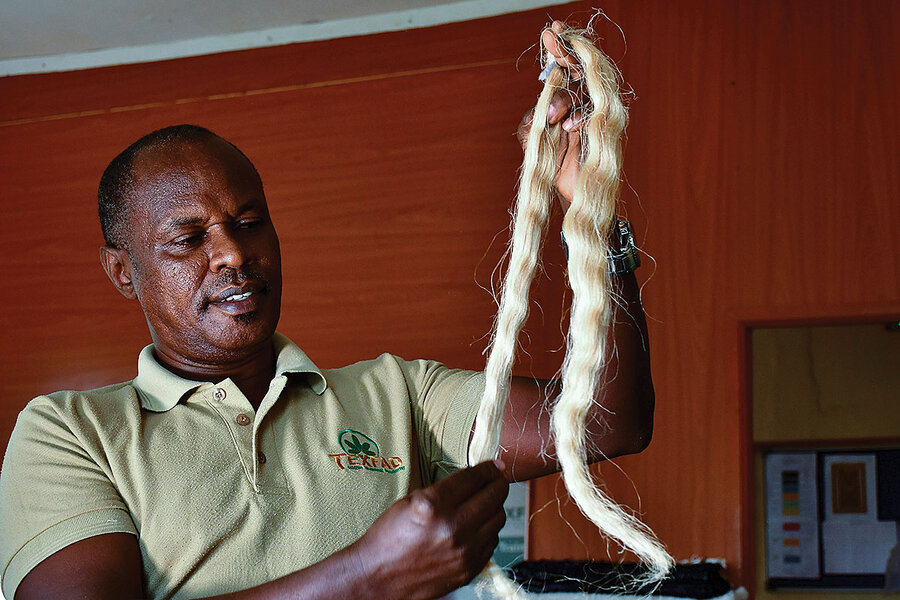

A volunteer for The Mango Project places mango slices in a solar dryer for preservation in Midigo, Uganda, where malnutrition is a serious issue.

One of my grandsons has had an interest in Uganda for several years — first, through learning about endangered mountain gorillas, then through helping support a start-up water business in the country. As a result, I pay extra attention to Ugandan news.

John Okot reports at the Christian Science Monitor about two brothers in Uganda who launched a mango initiative to help their neighbors.

“Francis Asiku’s plan to fight hunger in his village began, quite naturally, under a bountiful mango tree. It was 2011, and he had just landed his first nursing job at Midigo Health Centre IV in Yumbe district in northern Uganda. He was excited and joyful. But in his first month at work, Mr. Asiku was surprised to learn that what many infants and expectant mothers seeking care needed wasn’t necessarily medicine. It was nutritious food.

“He recalls one hot afternoon, in particular, when a young mother rushed into the health center with a 4-year-old child in her arms. Mr. Asiku hurried to help. He quickly diagnosed poor feeding as the root of the child’s problem. …

“He headed home on a dirt road in the inky-dark evening. When he spotted birds feasting on rotting mangoes along his path, a question struck him: Why were so many people in his community malnourished when it experienced two plentiful mango seasons a year?

“He raised the issue later that night with his younger brother, farmer Emmanuel Mao. Soon afterward, the brothers met with village elders under the huge mango tree where community meetings were held. That was the start of their nonprofit, The Mango Project, which distributes glass jars full of mangoes to schools, to health centers, and directly to hungry individuals.

“The toll of hunger in Uganda is staggering, according to the Global Hunger Index, a report published by several global nonprofits. Almost 37% of the population is undernourished, and about one-quarter of children have stunting, a condition that is associated with malnutrition.

“When Mr. Asiku and Mr. Mao met with the Midigo elders, [they said] the brothers needed to figure out a way to preserve Midigo’s abundant mangoes throughout dry periods, when they are scarce. …

“Mr. Asiku and Mr. Mao embarked on researching a simple way to preserve food. They began ‘jarrying’ – cutting fruit pulp into thin slices and putting them in a glass container of boiling-hot water and sugar. While canning is practiced throughout the world, many Midigo villagers can’t afford sugar, not to mention glass jars with secure lids. The relatively easy preservation method – and the brothers’ fundraising efforts to obtain the necessary supplies – delighted village elders. …

“The brothers initially collected mangoes that were scattered throughout the village, but have since expanded their initiative to preserve the fruit from their family’s ancestral land. The jarred fruit is safe to eat for up to a year.

“Mr. Asiku knows that the mangoes alone will not end malnutrition in the community, since humans need a balanced diet. But the initiative, he says, is a great start to breaking the hunger cycle in Midigo. …

“Irene Andruzu, who supervises one of the Midigo Health Centre’s facilities, says she receives at least 50 jars of mangoes monthly to help malnourished patients. During the pandemic alone, more than 12,000 jars of mangoes were distributed to health clinics and refugee settlements.

“Scovia Anderu, a social worker for Calvary Chapel Midigo, lauds The Mango Project for instructing villagers. She says that most villagers lack knowledge about nutrition and that there are few qualified personnel who can educate them on the subject at the grassroots.

“Zuberi Ojjo, the district health officer for Yumbe, [says] The Mango Project ‘reminds people of the importance of nutrition to our well-being.’ …

“One obstacle for The Mango Project is that charcoal, which is needed to heat the water used to sterilize jars, can be difficult to obtain. Since 2023, the government has banned commercial charcoal production in the northern region over concerns about the alarming depletion of trees there. Nevertheless, illegal, large-scale tree-cutting has disrupted weather patterns in the region, where communities rely mainly on agriculture amid erratic, unpredictable rainfall. …

“Mr. Asiku has found one alternate form of fuel. Over the years, he has been scrimping and saving, and last year he purchased a solar-powered dryer worth $600. Besides mangoes, he dries vegetables such as okra and eggplant to give to villagers.

“He hopes to distribute the food more widely as he acquires a license from the government to do so – and more dryers. He also has an orchard with 310 hybrid mango trees. This is meant to supplement the seasonal mangoes in case there is low supply because of damage caused by fruit flies.

“ ‘It’s fulfilling to see my people smiling at the end of the day,’ Mr. Asiku says.”

More at the Monitor, here.

Photo: Edwin Ongom, CURE International

Photo: Edwin Ongom, CURE International