Photo: Hufton+ Crow.

This affordable housing in New York was designed by the firm of famed architect Daniel Libeskind.

If you’ve spent your career catering to the wealthy, where do you go for other worlds to conquer? One architect turned to the poor.

The story is from Justin Davidson at Markets Today via MSN.

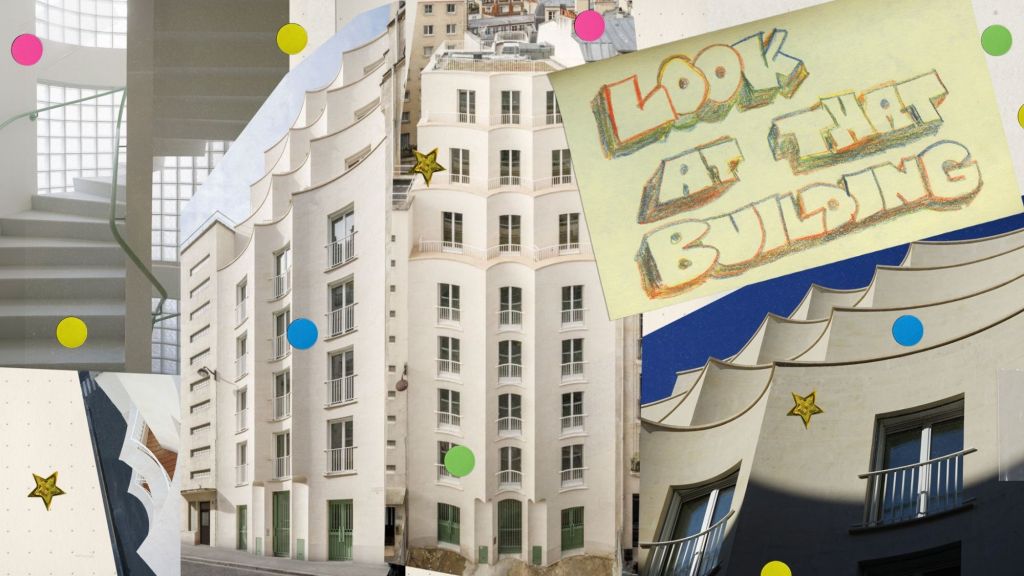

“Walk down an ordinary blah-colored stretch of Marcus Garvey Boulevard in Bedford-Stuyvesant, past the dispiriting bulk of Woodhull Hospital and the brown-brick boxes of the Sumner Houses project, and you come upon an incongruous apparition, a great white sugar cube that’s been carved, beveled, and knocked askew. Stranger still, this work of obviously ambitious architecture was executed on a spare budget for residents with meager incomes. Even more startling, the Atrium, an affordable-housing development for seniors and veterans of the shelter system, was designed by the firm of Daniel Libeskind, he … of the kind of jagged form that would defy attempts to gift-wrap it.

“With the Jewish Museum in Berlin, opened in 2001, Libeskind established himself as a pioneer of deconstructivism, a style based on the illusion that buildings were lifting off, bursting, imploding, or peeling apart. After the 9/11 attacks, when he was appointed master planner of the World Trade Center rebuilding project, he became famous as the embodiment of advanced architecture, headlining a period when a dozen or so celebrities scattered the world with signature structures. You might not know where a building was or what it was for or how it stood up, but you could quickly identify who designed it. His global brand would seem like an odd choice for the most basic tier of New York’s urban shelter. …

“Spend some time in and around the Atrium, though, and you begin to see that the pairing of high-design auteur and low-income residents meets an assortment of needs and isn’t just noblesse oblige. Erected by a cluster of nonprofits — Selfhelp Community Services, Riseboro Community Partnership, and the nonprofit developer Urban Builders Collaborative — on a patch of NYCHA [New York City Housing Authority] land, the Atrium leavens the neighborhood with 190 new apartments, a spacious community room, fresh landscaping, and a jolt of jauntiness.

“Like many public-housing projects, the original Sumner Houses, built in the late 1950s, withdraw from the street, lurking behind a perimeter of pointless lawn. The Atrium does the opposite, hugging the sidewalk, peppy and reassuring. This is an active, even restless building that greets passersby with a smooth dance move. … The whole structure makes a quarter-twist from ground to roof, and you can trace its sinews stretching diagonally across the grid of ribbon windows.

“Inside, comfortable apartments encircle the raised, skylit courtyard that gives the building its name. That arrangement is a resonant one for Libeskind, who grew up in the Amalgamated Houses in the Bronx, a complex developed in the 1920s by the garment workers union. …

” ‘It stood out,’ Libeskind told me. ‘It was populated by working-class people, but it had a sense of elegance.’ The courtyard was essential, a way for mostly Jewish immigrants to replace the tenement’s narrow, stinking air shaft with a form of genuinely gracious living. …

“Still, there’s a difference between an outdoor courtyard and an indoor atrium. Carelessly handled, the nine-story doughnut form could easily have evoked stifling precedents. … To avoid any hint of that oppressiveness, Libeskind laced the floor with diagonal walkways between raised planters and sculpted the inner façade almost like a climbing gym, with protrusions, ledges and trapezoidal windows placed in an apparently random arrangement. The goal was to make the court a destination rather than a vestibule. Since it’s one floor up from the lobby, going there requires an affirmative decision. …

“The success of a low-income housing complex depends on its social warmth. Selfhelp maintains a small team of social workers on-site, mostly to help residents navigate the welfare bureaucracy but also just to be there if they want to chat. …

“The residents I spoke to enjoy the Atrium, not because of its architectural pedigree but because it is clean and safe and orderly and bright, a rare haven for New Yorkers whose lives have often been turbulent. Still, loneliness is a tough enemy. …

“Designing a building and running it are different arts, but doing each one well fortifies the other. With the Atrium, Libeskind has given vulnerable people a place they can gradually make their own. He has also demonstrated that the daunting list of rules, requirements, prohibitions, and economic strictures that govern affordable housing in New York don’t have to choke off inventive architecture. …

“Ahmed Tigani, a deputy commissioner at the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, insists that the Atrium shouldn’t be a one-off showcase of precious design. Recruiting architects like Libeskind makes it clear that low-income housing is an integral part of the cityscape. City housing staffers should wrestle with loftier questions than those described by the number of units built, Tigani says. ‘What is the physical impact of our investment, but also the social and spiritual impact? What does a building visually contribute? Does it feel like a part of your neighborhood? Does it feel like a statement of belief in what that housing can be?’ ”

More at MSN, here.

Photo: Elizabeth Hafalia, The Chronicle

Photo: Elizabeth Hafalia, The Chronicle