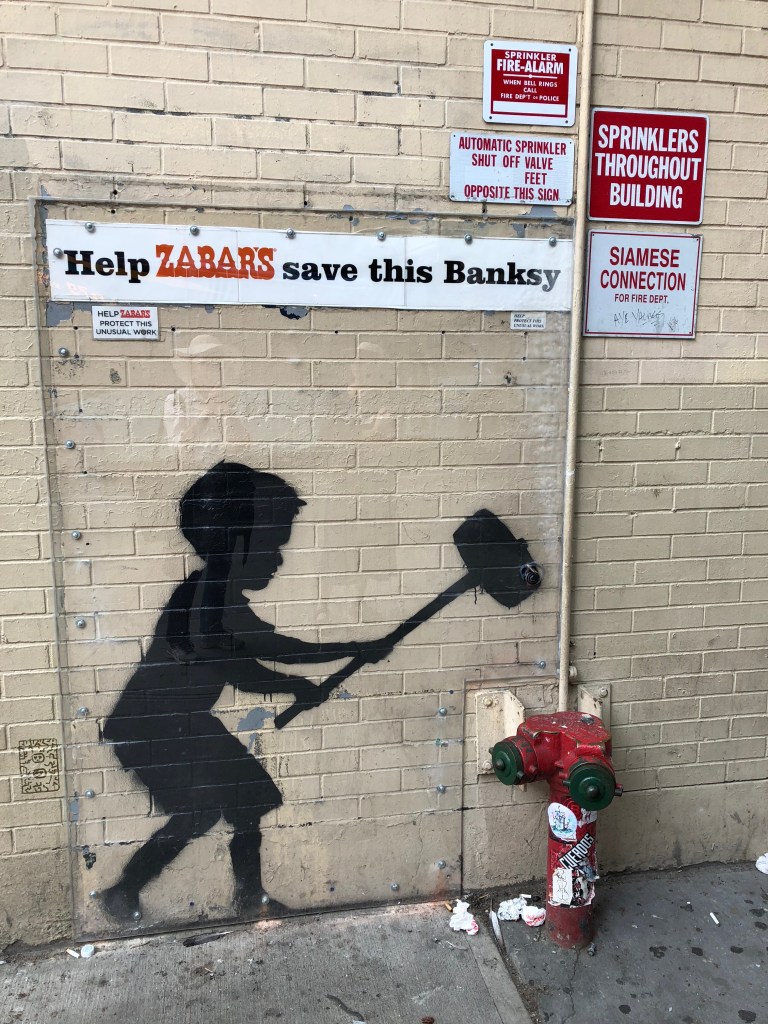

Photo: Tamara Merino/The Guardian.

Chilean muralist Alejandro ‘El Mono’ González compares the dimensions between his mock-up and a recent mural.

For a long time, I’ve been curious about murals and street art. (Search on those terms at the top of this blog if you are interested.) Whether the art is shared openly or under cover of darkness, it seems to convey messages we don’t usually hear from smaller, less public works.

At the Guardian recently, John Bartlett wrote that “in Chile, walls and public buildings are blank canvases to express dissent, frustration and hope.” Blogger and friend of Chile Rebecca will know all about that.

“Bridges across dry riverbeds in the Atacama desert,” Bartlett continues, “are daubed with slogans demanding the equitable distribution of Chile’s water, and graffiti on rural bus stops demand the restitution of Indigenous lands from forestry companies. Every inch of the bohemian port city Valparaíso is plastered with paint and posters. …

“One renowned street artist in paint-spattered jeans spent two weeks transforming a water tower at the country’s national stadium into a powerful symbol of Chile’s battle to remember its past.

“ ‘I have always had a strong social conscience,’ Alejandro ‘Mono’ González exclaims brightly. ‘The fight was born inside me, it just didn’t have an escape. There’s so much you can say with paint and a blank surface.’

“González, 77, has painted across Latin America and Europe, and his murals adorn hotels and public buildings in China, Cuba and Vietnam.

“González’s giant creations combine bright petals of color, separated by thick black lines, and resemble stained-glass windows.

“ ‘I wouldn’t say it’s cheerful, but they’re hopeful colors, which go beyond victimhood, pain and sadness,’ he said.

“The stadium was one of Chile’s most notorious detention centers, where thousands were held after Gen Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup d’état. …

“González talks animatedly about how colors vibrate and interact. … His approach reflects a selfless view of the collective.

“ ‘In the streets, anonymity is important,’ he says, ‘The individual isn’t, it’s the message that is interpreted by the viewer that I care about.’

“González was born in the city of Curicó, 120 miles (193km) south of Santiago, in 1947, the son of a laborer and a rural worker. At primary school, his friends named their energetic classmate ‘Mono’ – monkey. …

“After dark, González would go out painting with his parents, both committed members of Chile’s Communist party. In art, he found a release for his burning social conscience. González joined the communist youth ranks in 1965 to develop its propaganda activities, and painted his first mural at the age of 17 during socialist candidate Salvador Allende’s presidential campaign.

“He was among the founders of the Brigada Ramona Parra, a street art and propaganda collective named after a murdered activist, during the heady days of the Allende campaigns. ‘We’d go out every night, sometimes to paint murals, sometimes just to write ‘Allende’ on any blank surface,’ he remembers.

“After Allende won the presidency in 1970, a sinister black spider began to appear on walls, sprayed by the adherents of a fascist paramilitary group. A battle for the streets began, and it has never truly died away.

“In 2019, protesters thronged the streets of Chile’s cities demanding a host of improvements to their lives and an end to the country’s entrenched inequalities. … Those protesters included members of Todas, a collective of more than 100 female muralists who mobilized in a WhatsApp chat.

“ ‘We organized ourselves so we could occupy the walls,’ said Paula Godoy, 34, an artist and muralist from a southern Santiago suburb. ‘We were talking all the time – “Where is there a wall free? Where do we need to get this message across?” – it was a really beautiful period.’ …

“Half a century earlier, González was 24 when Pinochet seized power on 11 September 1973, deposing Allende. … González slipped into the shadows. He stopped wearing his glasses, shaved off his mustache, and went by the name Marcelo as he worked as a set designer in the Municipal Theatre in Santiago.

“When the end of the dictatorship neared, González helped design the most famous campaign in Chile’s political history, the NO campaign against Pinochet’s continued rule in a 1988 plebiscite. …

“ ‘Chile is very conservative and reactionary – we advance, and then we go backwards,’ he says, stepping back from the water tower and shielding his eyes. ‘But memory is the one constant. The most important thing is having a lasting effect. This will still be here in 50 years’ time, and people will still have their memory.’ ”

More at the Guardian, here. No firewall. Donations solicited.